“If only Vincent Sheean could persuade the Czechs…” (November 28, 1939)

by Mischa Richter (1910-2001)

10 x 14 in., ink and wash on paper

Coppola Collection

Mischa Richter (1910-2001) was a well-known New Yorker, King Features, and PM newspaper cartoonist who worked for the Communist Party’s literary journal “New Masses” in the late 1930 and early 1940s, becoming its art editor in the 1940s.

Just before that time, he worked in the WPA art project as a mural painter in New York. He then turned to cartooning, doing editorial and humorous cartoons for the daily newspaper, PM, and then becoming art editor for the New Masses.

The New Masses (1926–1948) was an American Marxist magazine closely associated with the Communist Party in the US. It succeeded The Masses (1912—1917) and later merged into Masses & Mainstream (1948—1963). With the coming of the Great Depression in 1929, America became more receptive to ideas from the political left and the New Masses became highly influential in intellectual circles. The magazine has been called “the principal organ of the American cultural left” from 1926 onwards.

In 1941 Richter began his longtime affiliation with the New Yorker, as well as producing daily panels, “Strictly Richter” and “Bugs Baer” for King Features. In the 1970s and 1980s, Richter did numerous drawings for the OpEd page of the New York Times.

But here we are in November 1939, less than three months after the Nazi invasion of Poland (September 1) that marks the start of WW2. This is not a drawing of the historical Hitler we have today, monstrous with the insight of hindsight. To many in 1939, he is an authoritarian despot with still-secret ambition for world conquest, benefitting from the surprising non-aggression pact with Stalin (Molotov-Ribbentrop Treaty, August 1939), the appeasement policy of British PM Chamberlain (“peace for our time”), and the radical isolationism of the US after WW1.

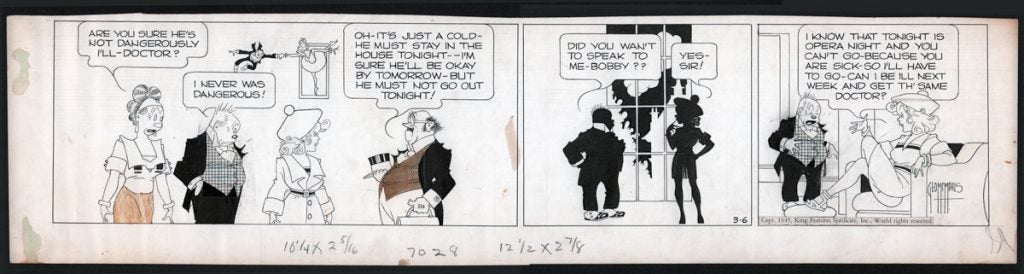

A despondent Hitler splays across a table and wonders “If only Vincent Sheean could persuade the Czechs that Communism and fascism are the same thing.”

So who is Vincent Sheean, and what is happening in Czechoslovakia in late 1939?

In 1918, Vincent Sheean (1899 – 1975) joined the US Army with the intention of taking part in the First World War, which ended before he served. “We felt cheated,” he says in his autobiography. “We had been put into uniform with the definite promise that we were to be trained as officers and sent to France.” He finished his degree at the University of Chicago in 1919, moved to New York City and began work for the Daily News. He lived in Greenwich Village where he associated with many left-wing figures who had reported on the 1917 Russian Revolution and the civil war that resulted in the rise of communism and the establishment of the USSR in 1923. In 1922 he visited Europe. He eventually settled in Paris where he became foreign correspondent for The Chicago Tribune.

Sheean published his autobiographical Personal History in 1935. The book tells the story of Sheean’s experiences of reporting on the rise of fascism in Europe. Sheean was highly critical of both Chamberlain and the US. His follow-up book, Not Peace but the Sword was published in March 1939, the same month that Czechoslovakia was invaded, and it was on the bookstands as a bestseller only weeks before the invasion of Poland on September 1. Both books focus on the rise of fascism in Germany, its parallel and at least sympathetic relationship with communism, and what he saw as a betrayal by England and France to not defend democracy more strongly. A fictionalized account of Personal History, which had been republished in 1940, was used as the basis for Foreign Correspondent, a movie by Alfred Hitchcock, also in 1940.

Hitler annexed all of Austria without firing a single shot in March 1938. His next target, as had been laid out in Mein Kampf, was the possession of the Sudetenland, the part of Czechoslovakia where millions of ethnic Germans lived. He announced in September 1938 that Germany demanded the “return” of all Czechoslovak lands where at least fifty-one percent of the population considered itself “German,” promising that war would soon erupt if his demands were not granted.

Journalists rushed into Prague, capital city of the Czech Republic, to report on the drama that unfolded over the following months. Among those who came to observe and report: Vincent Sheean. Sheean reported on September 21, 1938, having spent the day in the Sudetenland, that loud speakers posted throughout the city had just announced to the Czechs that under pressure from London and Paris, the government had accepted the German dictator’s demand for a revision of the two countries’ border. On September 30, 1938, Hitler, Mussolini, French Premier Daladier, and British Prime Minister Chamberlain signed the Munich Pact, which sealed the fate of Czechoslovakia, virtually handing it over to Germany in the (false) name of peace.

Chamberlain (September 1938): “My good friends, for the second time in our history, a British Prime Minister has returned from Germany bringing peace with honour. I believe it is peace for our time.”

Chamberlain is frequently misquoted as “peace in our time.”

Under European pressure, the Czech government attempted to appease Hitler: from dissolving the Communist Party to suspending all Jewish teachers in ethnic-German majority schools. As early as October 1938, Hitler made it clear that he intended to force the central Czechoslovakian government to give Slovakia its independence, opening up its dependence on Germany and putting the Czech state in greater jeopardy. And like clockwork, it happened. Slovakia declared its “independence” on March 14, 1939. And the next day, March 15, Hitler threatened a bombing raid against Prague unless he got free passage for German troops into Czech borders. He got it. By evening, Hitler made his entry into Prague.

Another easy conquest, with the stage set for his move on Poland. The secret terms of the August 30, 1939 non-aggression pact with Stalin (Molotov-Ribbentrop Treaty) outlined how Czechoslovakia and Poland would be divided between Germany and Russia, giving the Nazis their opening to invade Poland on September 1, which marks the historical opening of WW2.

Hitler continues to bamboozle England and France with promises of peace over the next few months. On October 28, thousands of people, mainly students, mark the 21stanniversary of the founding of Czechoslovakia. The Nazis retaliate by closing universities, executing student leaders and making many arrests. On November 17, the Germans stormed the university dorms in Prague and other towns in the former Czechoslovakia, attacking and arresting thousands of students, sending many of them to concentration camps. The Nazis executed nine Czechs by firing squad without trial that day for leading the demonstrations. On November 18, the Nazis closed all the technical schools.

Today, International Students’ Day is observed on November 17. This year, 2019, marks the 80thanniversary of the protests.

Richter’s cartoon expresses some anxiety by Hitler on how things are going in Czechoslovakia. And at the time, it might have looked like he was getting pushback from the Czechs, but we know in retrospect that the Nazis had the situation in hand.

It is worth noting that 2019 is also the 80thanniversary of Marvel comics (the original Marvel Comics #1 was published in October 1939 and featured both the Human Torch and the Sub-Mariner). In the 2015 movie, Avengers:Age of Ultron, Tony Stark explicitly and ironically uses the “peace in our time” phrase as something that could now be possible, as it was not before, because of the protective Ultron protocol he wants to put in place around the earth following the alien invasion seen in the first Avengers movie. Stark’s line of dialog: “peace in our time, imagine that.” His naïve arrogance inspires the now-sentient Ultron to repeat the quote, which is played back after Ultron takes a look at the madness of human history, as a mandate to exterminate human life as the only pathway to peace.

The huge sales of Marvel Comics #1 results in a second printing, with the October date removed, in November 1939, just as the situation in Czechoslovakia is unfolding and this cartoon appears in the New Masses.

The Age of Ultron allusion is a nice example of good writing, but there is just no way to clue the audience in to the Chamberlain reference. When you are aware of the significance of the quote, the scene reads quite strongly. In both cases, the quote ignores the implicit danger of the situation and precedes the threat of the villain in the story to end up carrying out a quite distorted version of “peace.”

The “peace in our time” phrase is infamous for representing ironic delusion, and (perhaps even more interesting) it is apparently tied to the origin of the phrase “killer joke.”

In October 1969, on the 30-year anniversary of Chamberlain’s pronouncement, a Monty Python sketch titled “The Funniest Joke in the World” is aired. The military potential of the “Killer Joke” is one that is so funny that anyone who hears it promptly dies. In the sketch, the “German translation” of the joke is used as a weapon during July 1944, causing the immediate death of soldiers in the field, and leading to victory in WW2. The German version of the joke is said to be 60,000 times more powerful than Britain’s great pre-war joke, at which point the famous video of Chamberlain waiving his copy of the Munich “peace for our time” Pact around, nailing the Pythoncommentary squarely on its head. The “Killer Joke” skit was reduced in time and popularized in the 1971 Python movie And Now for Something Completely Different.

Although I have never seen the following connection made, it is difficult to ignore. In March 1988, DC Comics published the landmark story Batman: The Killing Joke, which helped to shape the realism narrative of comics stories ever since, and includes controversial maiming, abuse and exploitation of Barbara “Batgirl” Gordon.

Joker tries to persuade Batman that the world is inherently insane and thus not worth fighting for. He knows he went crazy after learning how the world was just an awful joke. He rants how the Second World War was allegedly caused by Germany entering an argument over the amount of telegraph poles they owed the Allies when undergoing reparations shortly after the First World War. There is a “Killer Joke” in the story, and it is funny enough to make the normally stoic Batman laugh.

And just to close this tight, tight circle a bit more, the “funniest joke in the world” being “a joke so funny you will die laughing” is easily imagined to extrapolate from the common expression “to die laughing.” This is an old expression, which appears in Shakespeare [The Taming of the Shrew (3:2), ca. 1590: “Went they not quickly, I should die with laughing.”] and is accompanied by any number of hyperbolic things that happen when you laugh too hard (splitting your guts, having your head fall off, and so on).

Either the Python crew got an independent inspiration, or they were inspired by the comic strip writer Al Capp who, in 1967, has his Li’l Abner character uncover a joke so funny that you die laughing. Bob Hope makes an appearance in this story because he is looking to get the joke for his TV show.