Although Dave Sim committed to the 300 issues for the Cerebus the Aardvark series, he also maintains that the story he had in mind was summed up by the end of issue #200, making issues #201-300 one incredibly long epilogue to the story. It is true that all of the dangling threads in the overall mythos were wrapped up by #200, and Dave went all “meta” by entering the story as a character to make a point about the role of creators in stories and the control they have over their creations.

As the story is winding up, Cerebus is shown having an inner monologue with Dave. Dave plays himself, perfectly aware of himself as the writer and artist. Cerebus, on the other hand, is interacting with his creator, and has no context for understanding what that means. In fiction, this theme is the exact subject of a terrific book called “Flatland,” (Edwin Abbott, 1884) in which the inhabitants of a 2D universe cannot conceptualize what it is like to exist in 3D (in my comparison, delightfully, the comic book page is a 2D universe). The metaphor that Dave is playing out is more explicitly religious (although Flatland is about this, too), and he wants to make a point about how we cannot understand it, anyhow, when our creator is revealed to us. At this point, rather playfully, he imagines the creator could just as well be a couple of guys at drawing boards.

A whimsical creator is also not unlike the point that Philip K Dick makes in The Adjustment Bureau, or the compelling argument getting serious consideration that we all live in a Matrix-like simulation (because we are on the verge of creating VR/AI that is indistinguishable from our perception of reality, the odds of this being the first time it has been done are vanishingly small; and it turns out to solve some standing anomalies such as the finite speed of light and the observations of quantum entanglement).

The scenario at the end of issue #200 sets up what could have been a magnum opus 100-page parody on religious belief that might have rivaled “Life of Brian” or “Book of Mormon.” Things turned out differently, but that’s someone else’s story to tell. You want to see some old school Western fundamentalism in action, though? Google “Life of Brian – 1979 Debate” and pull up the 4 segments from the BBC program on YouTube; everything that happens after the two non-Python panelists show up is TV Worth Watching. Forty years is a long, and not so long, time ago.

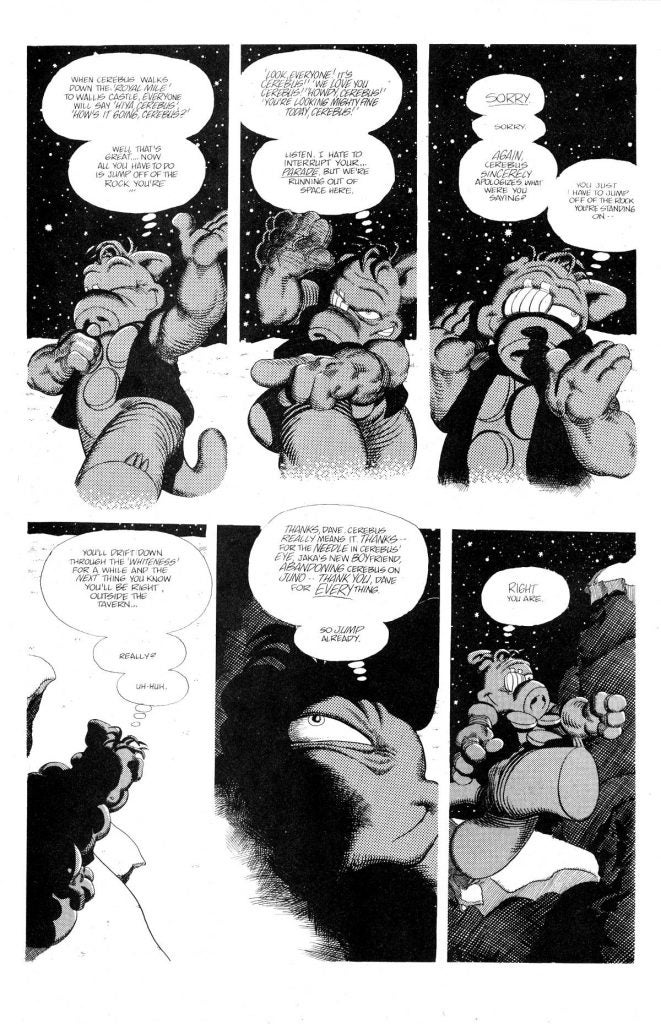

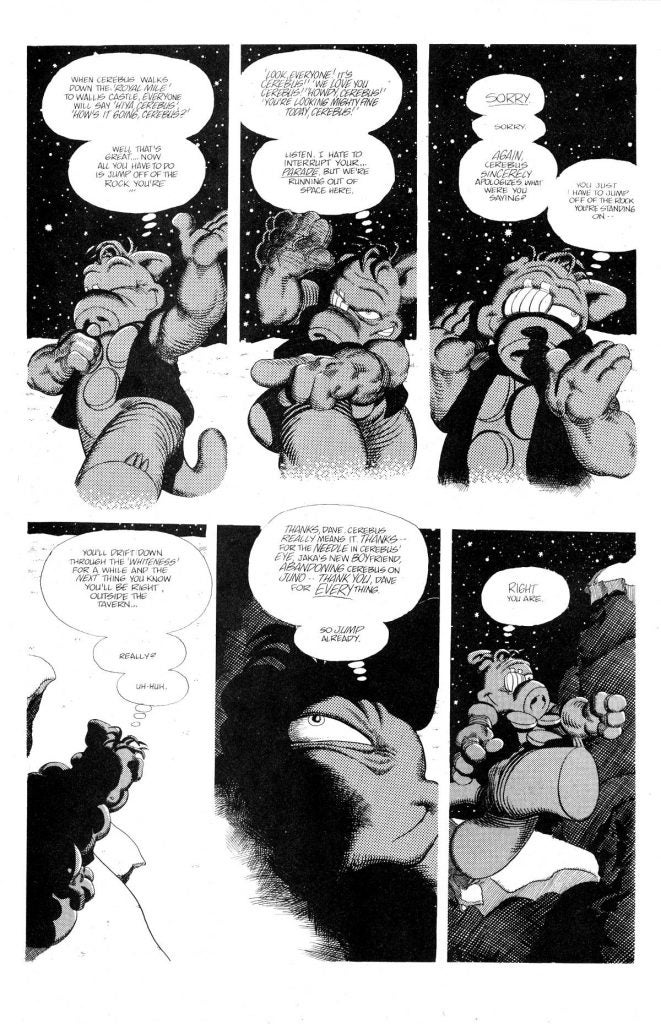

As issue #200 wraps up, Dave makes a point about how belief requires a leap of faith, which is what he asks his creation to do on page 17 (all of the copies of the pages here are courtesy of “Cerebus Downloads” as I do not own any of them; as of this writing, you can download all 6000 of so pages for USD $99).

Cerebus the Aardvark #200, p. 17

Dave (panel 1): Now all you have to do is jump off the rock you’re…

Dave (panel 2): Listen, I hate to interrupt your… parade, but we’re running out of space here.

Dave (panel 3): You just have to jump off the rock you’re standing on…

Dave (panel 4): You’ll drift down through the “whiteness” for a while and the nextthing you know you’ll be right outside the tavern…

Dave (panel 5): So jump already.

Turns out, when you see things from the creator’s perspective, things are different than from the creation’s. That white space is the white space of the drawing board, and the creation (in the mind of the artist) is running through this narrative and you (the creator) get to decide what gets codified.

As a creation (if you accept that you are a creation, but let’s run with that for a moment), then Dave’s proposition is that you cannot know the mind of your creator because your perspectives are so different (another assumption, but let’s run with that for a moment). Cerebus (the creation, living in a 2D universe) cannot get past the things that he knows (his 2D perspective) and cannot even begin to understand the references made by his creator in the 3D universe (we are “running out of space” in this issue of the comic book you are in, for instance). So you hear what you hear and understand whatever clues you can make out from your creator, and when it comes time, you just have to take a leap of faith. Dave’s proposition, not mine, on the consequences of page 17.

I will most leave aside for now: (1) that you have to accept you are an intentional creation, (2) that you cannot know the mind (perspective) of your creator, and (3) that taking the leap of faith is ultimately hypocritical to these assumptions because you are still making a guess about the unknowable mind of your creator. More about that in a moment.

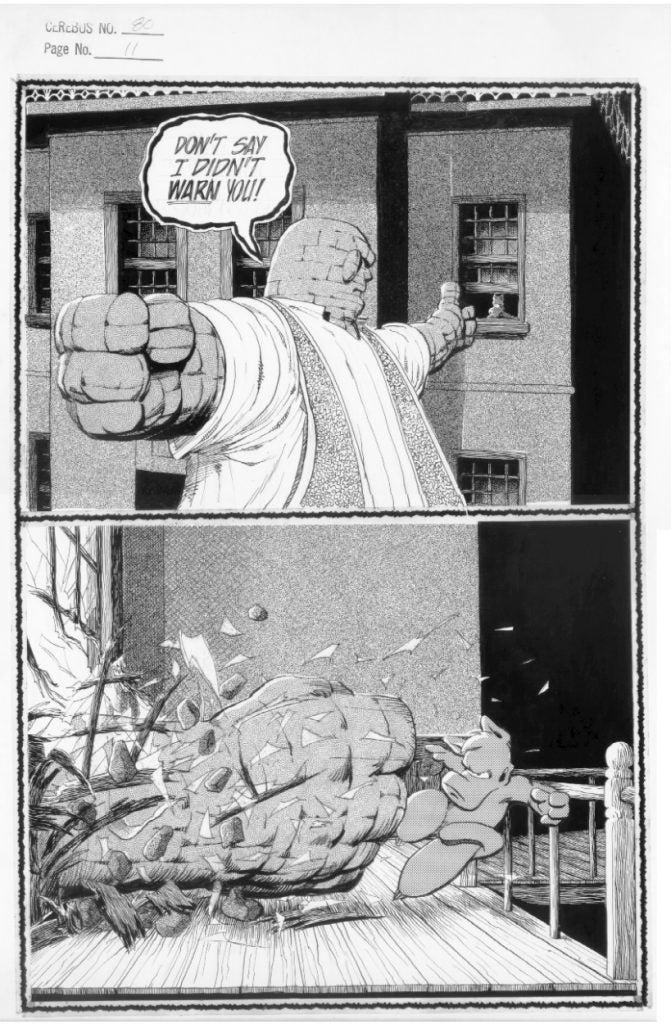

Which brings us to one of my favorite comics pages ever: page 18.

Cerebus the Aardvark #200, p. 18

Cerebus takes his leap of faith. And he’s codified on the first panel. But now we see life from the mind of the creator, and we realize that what had been codified is also dynamic. The top panel captures the fall, and the fall continues. Dave crunches a carrot at the codified panel, but a moment later, in panel 2, Cerebus is tumbling and Dave is chewing as time is moved forward. Cerebus tumbles, Dave finishes the carrot, and tosses the stogie past Gerhard. All captured on the page that is on the page, ad infinitum. Have you seen the intro to the terrific series “Black Mirror”? This is the point where you see the >crack< happen.

On page 19, we are fully in the creator’s world. The creator is out of the shadows and revealed. The page is done and everything is in synch (note the lack of tone in the Cerebus figures; this is now “just” the drawing, in contrast with the imagined reality on the previous page).

Cerebus the Aardvark #200, p. 19

And what is Dave’s take on three assumptions, here? I think he comes down squarely on the side of the assumptions of religious belief being (1) that you have to accept you are an intentional creation, (2) that you cannot know the mind (perspective) of your creator, and (3) that taking the leap of faith is ultimately hypocritical to these assumptions because you are still making a guess about the unknowable mind of your creator. Dave is playing the role here of that famously historical philosopher, Bugs Bunny (note the carrot), and quotes the bunny from the endless situations where he has duped an antagonist into a leap of faith and bending to his will: (to quote the bunny) “what a maroon… what an ultra-maroon…” This page and its mocking is critical to understanding the message. Taking your belief that you can know the mind of your creator (and listen) and that what you need to do is take a leap of faith (and follow) is just another unknowable thing, not a legitimate conclusion.

And do not even get me started on whether the audience is created by the author, or vice versa, cuz a tree just fell in the woods (heh… something fell).

Some other day, we can follow through with the creation/creator assumption and decide whether or not a creation can have free will or not. Cerebus is told that his action is a leap of faith, but in reality it is predestination, literally at and in the hands of his creator. This scenario was setting up a direction for a meditation on religious beliefs that later ended up (in the words of the bunny) taking a left turn at Albuquerque.

And on page 20, a little reminder as the carrot has landed and the epilogue kicks off.

Cerebus the Aardvark #200, p. 20

Next: A New Reality

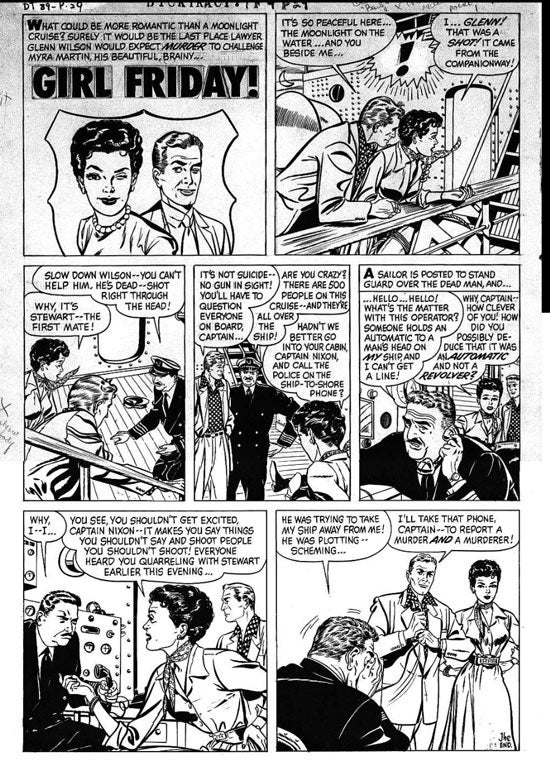

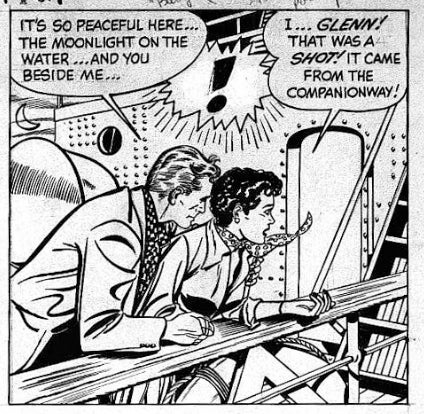

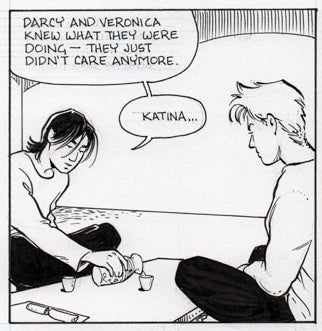

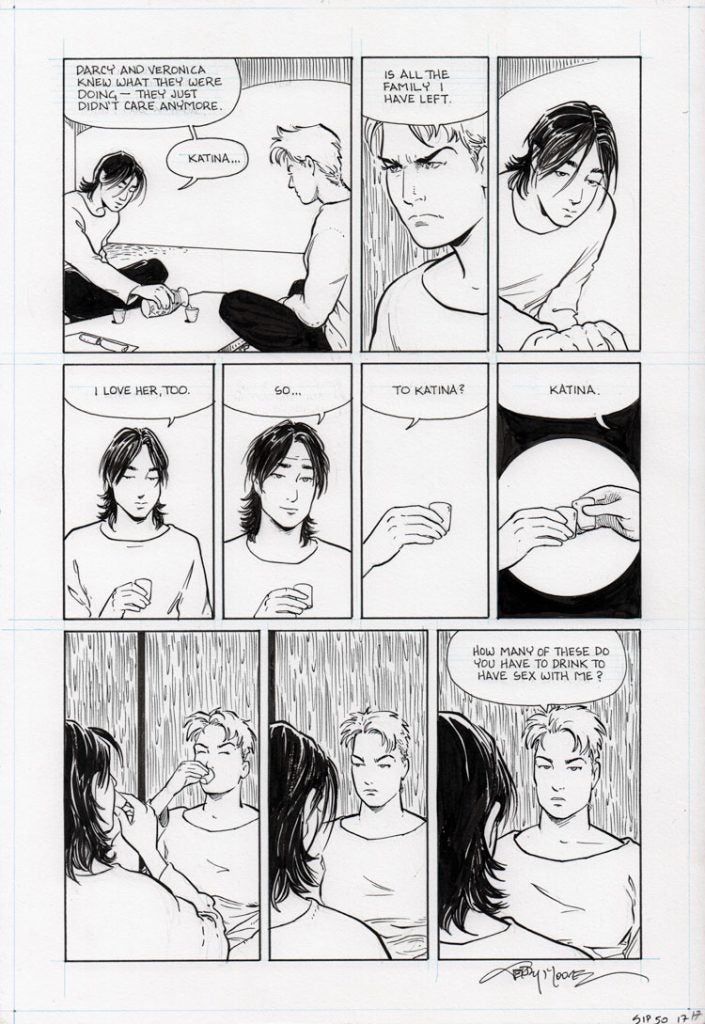

Dr. Frederick Wertham, a German psychologist, is a well-known figure in the history of comic books. His lack of appreciation of scientific evidence to advance an idea is infamous: because 95% of kids in reform schools in the late 1940s read comic books, comic books are a prime cause of juvenile delinquency. And the eventual release of his primary materials for study, in 2010, also presents a case for him manufacturing and distorting the evidence he actually had. Wertham’s positions: The horror and war genres promoted violence, drug use was rampant in the comics, the shameful representation of women and sexual innuendo promoted promiscuity, and everyone “wink-wink” knew that Batman and Robin were gay and that Wonder Woman, filled with strength and independence, was clearly a lesbian. Wertham’s 1954 book, The Seduction of the Innocent, lays out his case. Wertham’s credentials made him a star witness at Senator Kefauver’s 1953-54 Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency.

Dr. Frederick Wertham, a German psychologist, is a well-known figure in the history of comic books. His lack of appreciation of scientific evidence to advance an idea is infamous: because 95% of kids in reform schools in the late 1940s read comic books, comic books are a prime cause of juvenile delinquency. And the eventual release of his primary materials for study, in 2010, also presents a case for him manufacturing and distorting the evidence he actually had. Wertham’s positions: The horror and war genres promoted violence, drug use was rampant in the comics, the shameful representation of women and sexual innuendo promoted promiscuity, and everyone “wink-wink” knew that Batman and Robin were gay and that Wonder Woman, filled with strength and independence, was clearly a lesbian. Wertham’s 1954 book, The Seduction of the Innocent, lays out his case. Wertham’s credentials made him a star witness at Senator Kefauver’s 1953-54 Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency.