“Gale Winds” (1961)

“Gale Winds” (1961)

by A. B. Chapin (1875-1962)

13 x 13 in., ink on paper

Coppola Collection

Archibald B. Chapin was a renowned editorial cartoonist in the Midwest. He spent his early career in Kansas City, St Louis and Philadelphia. In 1942, he moved to Schenectady, New York, and drew a weekly cartoon for the National Weekly Newspaper Service. He died October 19, 1962, which means he was certainly staying active as an editorial cartoonist into his late 80s.

This is a striking composition, the subject of which is a strong reminder that the US was hip deep in SE Asia long before the Vietnam conflict.

The Laotian Civil War (1953–75) is called the Secret War among the CIA Special Activities Division and among veterans of the conflict. Early on, North Vietnam established the Ho Chi Minh Trail as a paved highway in the southeast of Laos and paralleling the Vietnamese border. The Trail was designed to allow North Vietnamese troops and supplies to infiltrate the Republic of Vietnam, as well as to aid the National Liberation Front (Viet Cong).

On August 9, 1960, the Laotian Neutralists seized control of the administrative capital of Vientiane in peaceful coup. The US CIA helped support a counter-coup, supplying artillery, artillerymen, and advisers to the rebel forces.

The Soviet Union began a program of military air support for the Neutralist/Communist coalition in early December, 1960; it was characterized as the largest Soviet airlift since World War II.

The US-backed counter-coup was successful, but the end result was the strong alliance of the Neutralists with the Communist Pathet Lao. As 1960 ended, the nation of Laos had become a theater for the world’s superpowers. The Russian Soviet air supply continued into the new year, and the North Vietnamese presence was escalating.

The incoming Kennedy administration found itself pitched immediately into the Laotian crisis. An inter-agency task force founded in early February began a two-month study of possible American responses to the Laotian war. The most drastic alternative they envisioned was a 60,000-troop commitment of American ground troops in southern Laos, with a possible use of nuclear weapons.

Throughout the year, tensions mounted as skirmishes continued.

A large strike involving B-26s had been scheduled, but the it was stayed by an event on the far side of the world. The Bay of Pigs Invasion failed, and that failure gave pause to US actions in Laos. A ceasefire was sought.

The truce supposedly went into effect the first week of May, but was repeatedly breached by the communists.

“Bloom County (09/02/1983)”

“Bloom County (09/02/1983)”

“Bernadotte and Napoleon” (1931)

“Bernadotte and Napoleon” (1931) Fantastic Four 124 p 4 (July 1972)

Fantastic Four 124 p 4 (July 1972) “Golden Series: Bosc Pear, Concord Grapes, Idiazabal Etxegarai (Spanish Cheese), Knife, and Italian Plums” (2017)

“Golden Series: Bosc Pear, Concord Grapes, Idiazabal Etxegarai (Spanish Cheese), Knife, and Italian Plums” (2017)

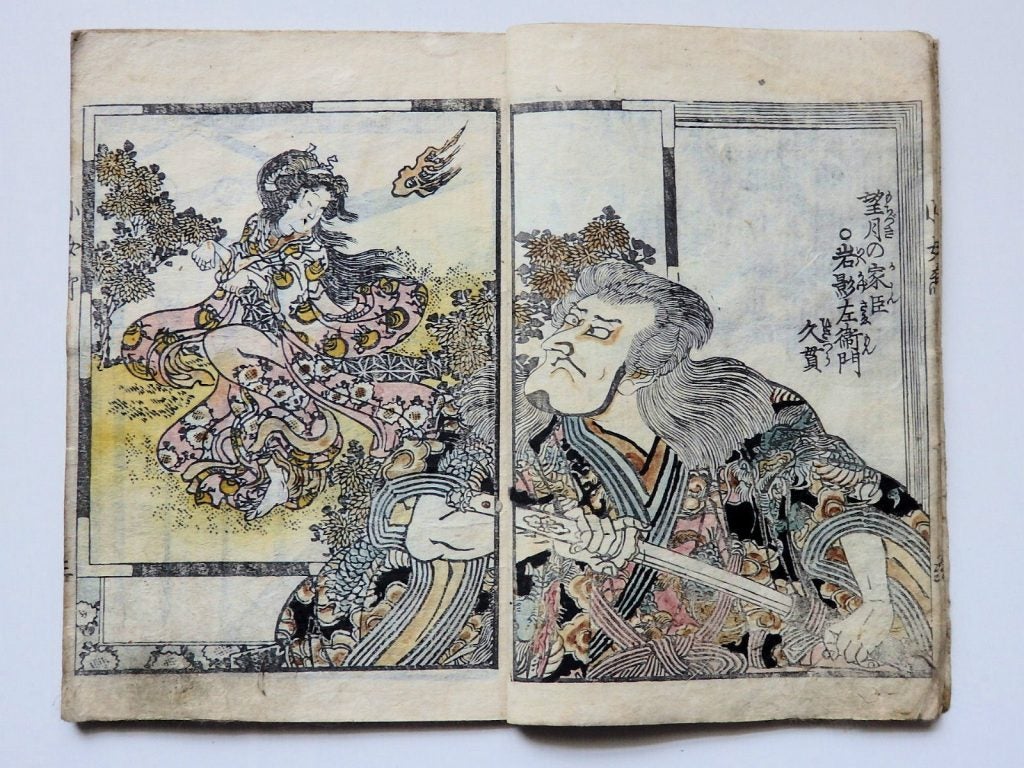

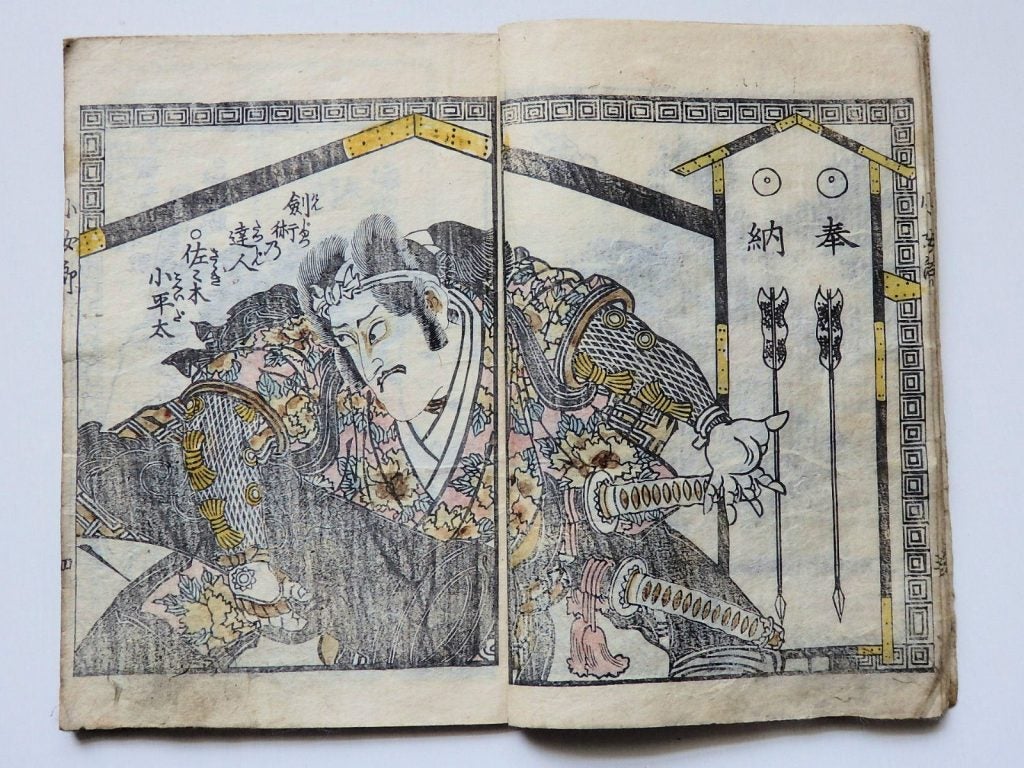

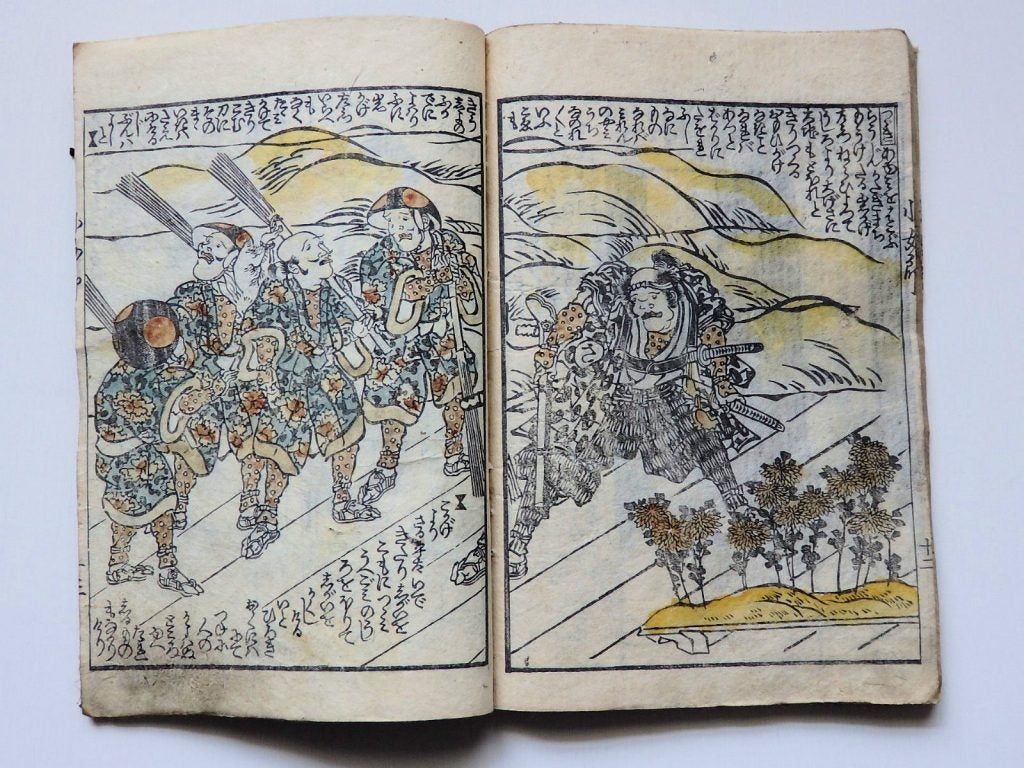

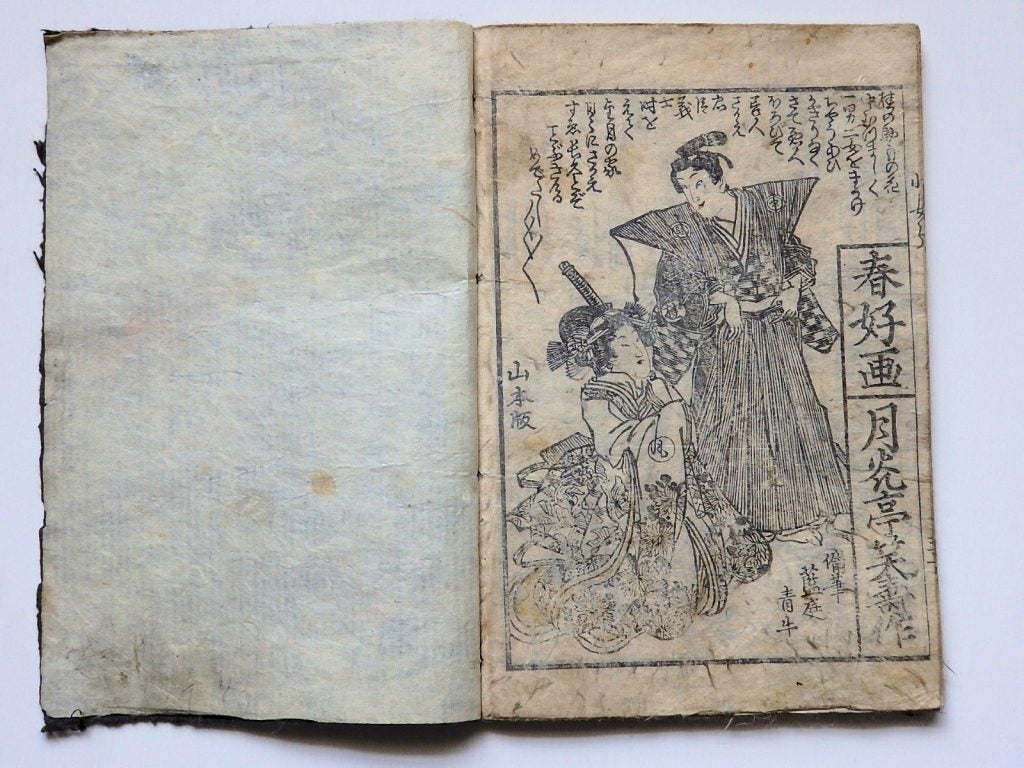

“Kojorokitsune Tebiki-no-Adauchi” (1822)

“Kojorokitsune Tebiki-no-Adauchi” (1822)

“Peanuts” (July 31, 1983)

“Peanuts” (July 31, 1983) “Gale Winds” (1961)

“Gale Winds” (1961) “Windswept” (2017)

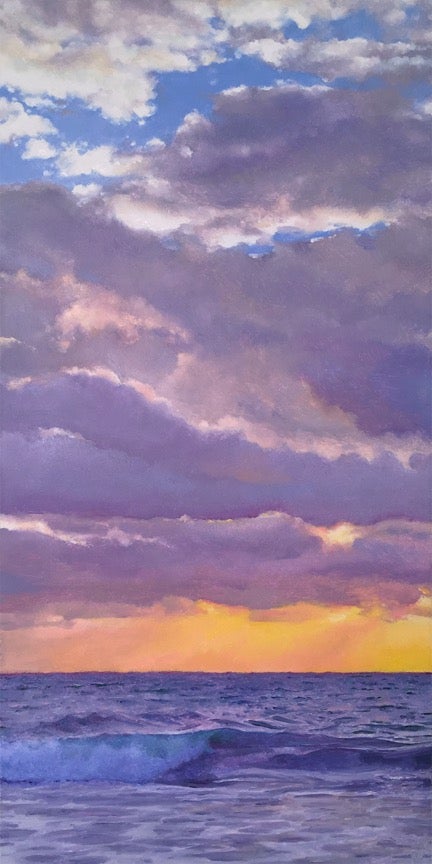

“Windswept” (2017)