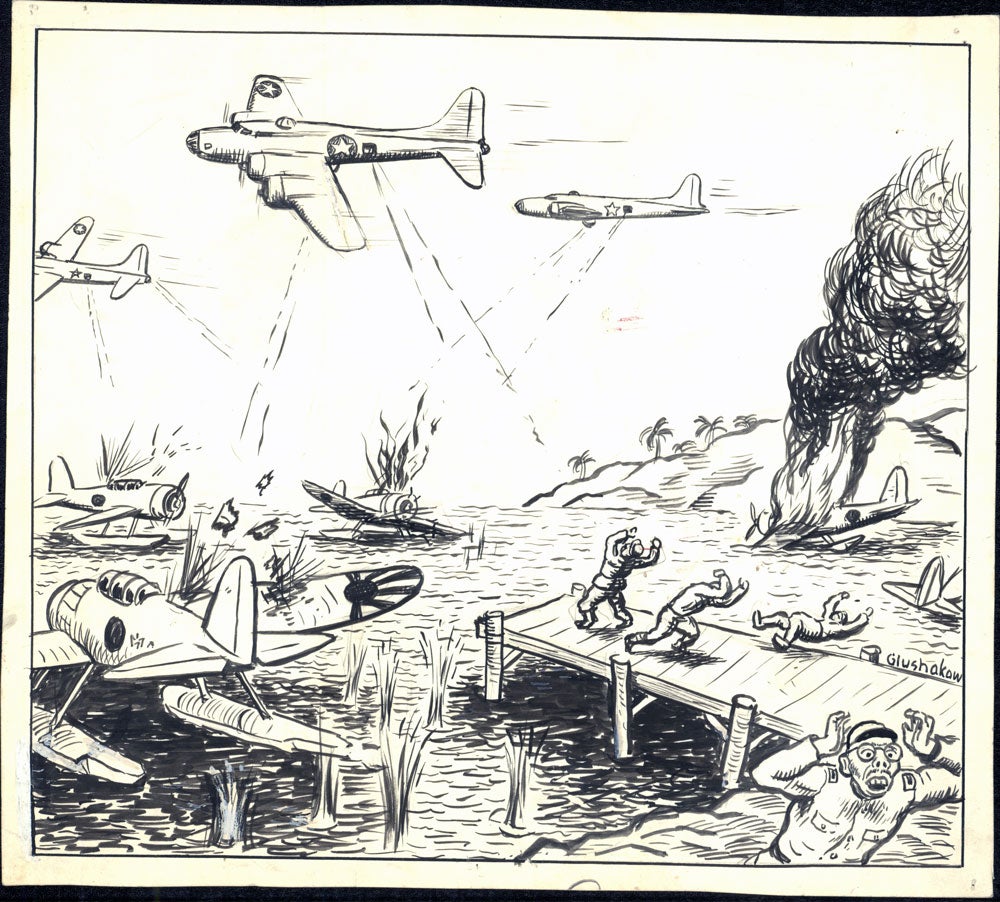

“The New Disorder” (Summer, 1943)

by Jacob Glushakow (1914-2000)

12.5 x 14 in., ink on board

Coppola Collection

Jacob Glushakow was a famous Jewish artist who lived in Baltimore, MD, who spent most of his life creating numerous drawings of the Baltimore area. He graduated from the Baltimore City College high school in 1933 and went on to the Maryland Institute College of Art and the Art Students League in New York, where he studied from 1933 to 1936. Jacob enlisted in the Air Force (December 17, 1941) and eventually served as a sergeant in England. On his enlistment materials, he is listed as an artist.

Jacob was initially trained and stationed at the Davis-Monthan (D-M) Air Force Base in Tucson, AZ. There are local newspaper reports in the Tucson Daily from June 11, 1942 (a painting of the Air Base selected to appear in the issue of Life Magazine during the first week of July); June 17, 1942 (painting signs for an Benefit Dance); and October 9, 1942 (a portrait of MacArthur unveiled, and working on a mural).

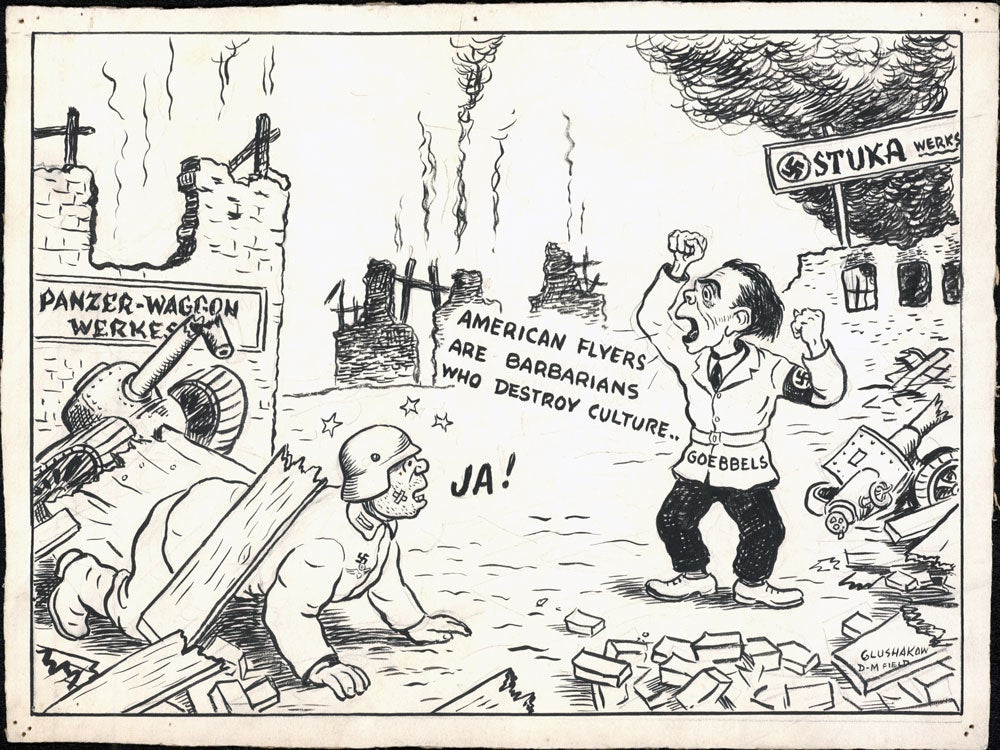

I have four of his cartoons, which I conclude were done for the Davis-Monthan Base newspaper. They say “Davis-Monthan” or “D-M Field” along with his name. One of them has a printing order sticker on the back with Davis-Monthan as the source. And if you look at the inferences you might draw from the topics in the cartoons, they could all reasonably fall in the last half of 1943, although that is speculation. They are not dated and there is no source publication to check. I also speculate that these must have been in his material belongings and released to auction by the family after he died. The Maryland Historical Society and the Jewish Museum of Maryland both have his works featured.

This cartoon looks like the summer of 1943. Threats to invade Italy began in May, following the Allied victory in North Africa. The mainland invasion was in September, following the taking of Sicily in July.

A Russian counter-attack during this period took place during the Kursk incursion. After failing to take Stalingrad, Hitler turned to Kursk to mount the next blitzkrieg offensive. The Nazi army could not penetrate the Soviet defenses, and in July, the Red Army launched a counter-offensive, Operation Kutuzov.

Worried by the Allies’ landing in Sicily on July 10, Hitler made the decision to halt the offensive action with the Soviets, and shifted to holding as much ground as possible in a defensive posture that lasted until August. Kursh would be the last large-scale action undertaken by the Wehrmacht.