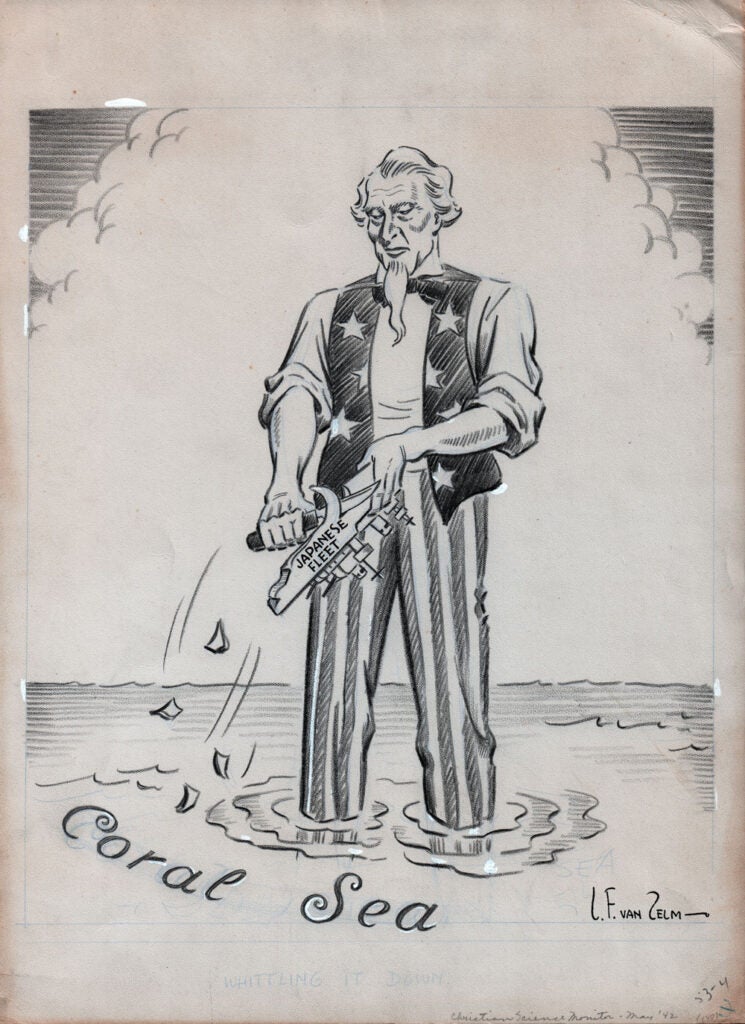

1941.05.12 “Whittling It Down.”

by Louis Franklin Van Zelm (1895-1961)

11 x 15 in., ink on board

Coppola Collection

Published in the Christian Science Monitor. Born in NY and educated in parts of New England and New Jersey, Van Zelm was VP of a metal company in 1920, drawing on that side for the New York Evening World (“Rusty and Bob”).

During the 1920s he contributed cartoons to the Larchmont Gazette, and drew “Such Is Life.” A 1925 issue of The MIT Technology Review noted van Zelm’s career changed: “All the yellow journals through the Middle West in mid-December printed long stories to the effect that L.F. van Zelm, whom we all remember as the best little cartoonist we had during our days at the Institute, has deserted architecture for cartooning, and is now cleaning up hordes of shekels as the perpetrator of a comic strip which makes a daily appearance in the dailies throughout that section. I feel sure all the gang join me in wishing Van the greatest success.”

He worked for the Christian Science Monitor from 1940-47, and then off and on again for the rest of his life. It was reported that on February 20, 1955, van Zelm filled his 50-room house, an old hotel, with gnomes and elves, and drew the daily cartoon, The VanGnomes, for the Christian Science Monitor. In 1958 he produced the strip Farnsworth.

The Battle of the Coral Sea, from May 4-8, 1942, was a major naval battle between the Imperial

Japanese Navy and naval and air forces of the United States and Australia. Taking place in the Pacific Theatre of World War II, the battle is historically significant as the first action in which aircraft carriers engaged each other and the first in which the opposing ships neither sighted nor fired directly upon one another.

The US learned of a Japanese plan through intelligence and sent two US Navy carrier task forces and a joint Australian-American cruiser force to oppose the offensive.

Although a tactical victory for the Japanese in terms of ships sunk, the battle proved to be a strategic victory for the Allies. The battle marked the first time since the start of the war that a major Japanese advance had been checked by the Allies. More importantly, two of the Japanese fleet carriers were damaged enough to be unable to participate in the Battle of Midway the following month.