A Cruise Ship is safer than a Campus

The optimism for re-opening campuses to in-person activity in the fall is being cast as “cautious” and “guarded” and “prudent,” which are all the new euphemisms for reckless and unsafe. The only situation about the pandemic that has changed since mid-March is the behavior of people, who isolated from one another to interfere with the only thing that could be controlled: the physical transmission of the coronavirus. The behavior of the coronavirus is unaffected. The epidemiology of outbreaks remains unaffected. The greater the crisscross of contacts with other humans, the more likely transmission exponentiates into an outbreak. The closed and close-quarters environments of cruise ships and food processing plants are the proofs of concept. And a cruise ship is safer than a campus.

Welcome to the S.S. University. Most of the 45,000 passengers are drawn from every state in the union, rural and urban, each carrying whatever contacts they left when they set out for the ship, as well as every contact along the way to embarkation. The boat is parked, and only a fraction of the passengers actually stay in their small, randomly-assigned, double-occupancy rooms. The S.S. University is not isolated. It is surrounded by an archipelago of neighborhoods and a flotilla of other boats. The passengers who do not live onboard this cruise of young and eager singles live in a community of smaller boats that ring the main ship, typically in 3-6 person groups in apartment cruisers.

Passengers live on the ship, off-boat passengers live in the apartment cruisers, and the entire staff, from the captain to the deck hands to the cruise directors to the custodial staff, all commute in from a hundred nearby islands. The people who live onboard and close by move back and forth, taking crowded ferries that pick up and drop off passengers from meeting site to meeting site. Every member of the staff and crew leave from and return to their families every day, and all the contacts that they have, embarking and disembarking daily.

The S.S. University is not the only destination. Among the archipelago and the flotilla of other boats, there is a constant crisscrossing that takes place, mainly around socializing and commerce. Some of the services of the S.S. University are exclusive to its onboard passengers, but many other services ring the wharf and are open to whomever can get there: bars and gyms and restaurants and coffee shops that are built around cheap prices and high turnover, because many of the passengers need to watch their money, are also attractive to the members of the archipelago.

Outside of the social agenda, the actual paid-for cruise for passengers is built around side-by-side meeting rooms and a tight schedule, with 10-minute changeovers in narrow corridors with access through a finite number of human-sized doors (each with a handle). The air circulation can be non-existent, often in rooms with no windows that, anyone can tell you, linger with the distinctive humidity of anxious humans after the first meeting of the day.

Everything is communal: the ferries that move passengers and staff around, the meeting rooms, the seats in the rooms, the materials used by the staff in the rooms, and every bathroom. Have you seen what the bathrooms are like by the afternoon?

Distancing is the beginning, not the end, of safety in the pandemic. Distancing is a way to think about contact in the present, only. How to maintain distance when you take commuting and the integration of time into account? Occupying spaces that need to be made safe before and after occupancy is another aspect of distancing: distancing in time. It does not matter that you are six feet away in the room when you are sitting in the seat for which there is no practical way of ensuring its safety, including from the passenger from the last session who sneezed onto its emptiness and caused the blood pressure of everyone else in the room to spike. Nearly all rooms have at least two doors, so you might manage “in” and “out” – but it is a pretty magical 10-minute ballet if everyone moving “out” can distance from everyone moving “in” as well as from one another.

Some fraction of the highly experienced staff is either at-risk or interacts with an at-risk member of their own family or might come across someone while taking care of business over the weekend back at their home island. Personally, I am a session leader for one of these activity rooms. And as much as I loathe to admit it, I am at risk. I am 63, male, a type II diabetic, and carry a genetic hypercoagulative disorder. When I enter one of those session rooms, I can invariably smell the departing group and sense its humidity. I see every surface, in front of me, that has been used by my colleague from the previous session. My colleague who is standing there, quite unavoidably, needing to spray their words to the student with a question after class to cover the noise of the changeover and their attempts to stay distanced. I do not want to put that mic on, and I really have no interest in touching the 4-5 buttons I need to touch just to get ready for my session.

A cruise ship is safer than a campus. I need a better metaphor. Navigating a campus in a pandemic is more comparable to every big heist movie you have ever seen. You do not just worry about the size of the bag you need in the moment you squirrel away the diamonds in the vault. You need to get in without being caught. You need to get out. You need to assume every surface and space has an alarm, so you better be prepared. Every single member of the team has a job to do, and you need to have trust in every other team member and in their skills, because your life is in their hands. And in this case, hundreds of different teams are carrying out their own heists in the same space as you, so your trust and confidence needs to exponentiate like a viral contagion. Before a heist, in the movies, you practice again and again in a simulated space, making the inevitable errors you make when you do something new, even when you are an experienced scoundrel. There is no room for rookies on your team.

In the campus pandemic heist, though, everyone is a rookie. The first bell rings on the first day, and you are following imagined instructions about how to proceed, procedures developed by senior management, whose memory of being an on-the-ground team member might not actually be from your campus or have taken place in the last two decades. In the 1981 noir film “Body Heat,” an experienced criminal played by Mickey Rourke is giving advice to a lawyer, played by William Hurt, who is contemplating pulling off a murder. Rourke returns the advice that Hurt once gave to him: “Are you ready to hear something? I want you to see if this sounds familiar: any time you try a decent crime, you got fifty ways you’re gonna fuck up. If you think of twenty-five of them, then you’re a genius… and you ain’t no genius.”

Are you contemplating in-person instruction this fall, in the absence of completely reliable testing, tracking, and a deep understanding about the mechanism of transmission of the coronavirus, particularly among the asymptomatic? If there is even one problem related to re-opening campus in this essay that had not occurred to you (did I mention that the toilets are all communal?), then heed Mickey Rourke’s advice about the hubris of genius. And believe me: I ain’t no genius. There are a countless number of unanticipated problems just waiting to turn your “guarded” and “cautious” optimism into reckless and unsafe actions.

Postscript:

The epidemiologists tell us to watch out for these variables in the equation of infectious exposure: space (farther apart, not closer), time (the lower, the better), people (the fewer, the better), and place (open, not closed).

That, and a heaping helping of common sense from Robert Strauss on how to behave when you are having a fight with a more powerful adversary:

You don’t quit when you’re tired – you quit when the gorilla is tired.

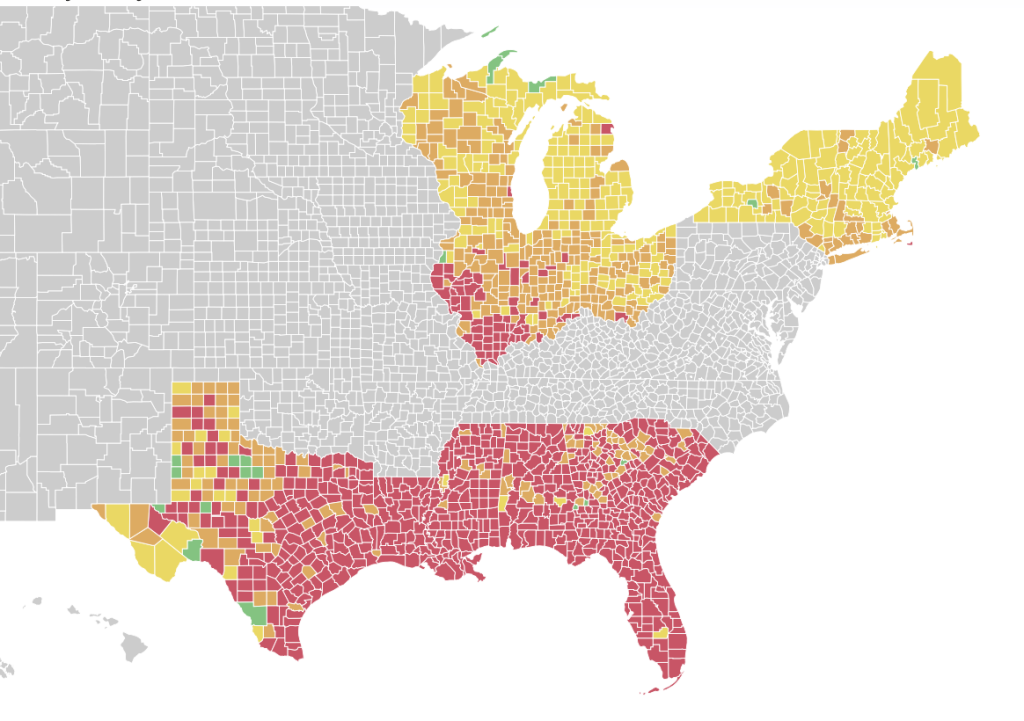

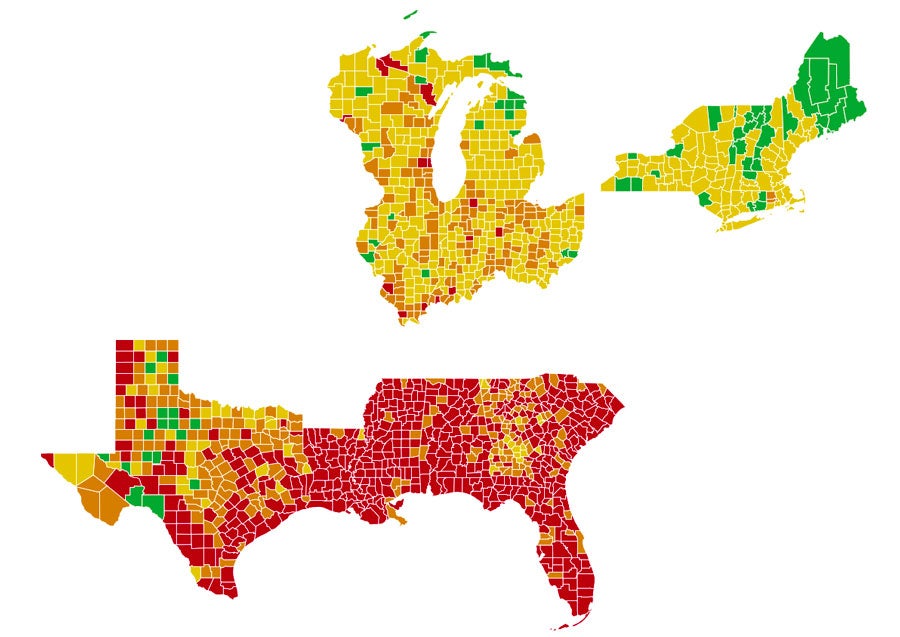

December 27, 2020 (Michigan gets a little credit here):

December 27, 2020 (Michigan gets a little credit here):