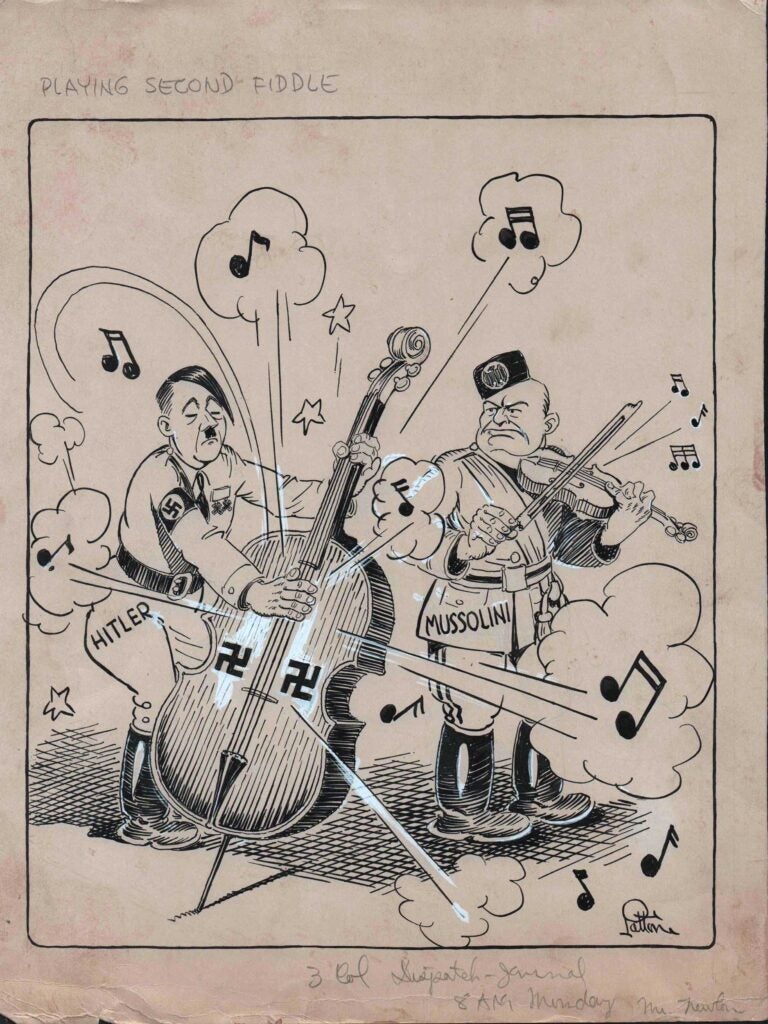

1941.02.15 “Playing Second Fiddle” (February 15, 1941)

by Jack Patton (1900-1962)

12 x 14 in., ink and crayon on board

Coppola Collection

Jack Patton was originally from Louisiana. He worked as an editorial cartoonist from the 1910s through the 1930s. In the 1930s, he was a widely read editorial cartoonist for The Dallas Morning News. His last editorial cartoons appeared at the end 1939 and perhaps through the start of 1940. During the 1930s, he also began the newspaper strip ‘Restless Age,’ which was followed by ‘Spence Easley’.

As a child, Patton read a magazine advertisement offering easy lessons in drawing. He signed up for a brief course, and it was enough to whet his appetite for a lifetime of cartooning. Scraping together enough money to get to Chicago, he enrolled in the Academy of Fine Arts. While at the school, he received word that the old Dallas Journal, then the evening publication of The Dallas News, needed an assistant in the art department. Hurrying back to his hometown, Mr. Patton found to his delight that he would work with veteran News cartoonist John Knott. The year was 1918 and two years later his editorial cartoons won a place on page 1 of the Journal. In the early part of his career, Mr. Patton was one of the first men in the business to put out both an editorial cartoon and a comic strip daily. The editorial cartoons had a stinging wit, and the originals were frequently requested by the subjects, including Franklin D. Roosevelt, Herbert Hoover and John Nance Garner.

The “second fiddle” relationship was clearly perceived at the time, and not just in the retrospective analyses written in the modern age. It was not only an apt metaphor, but probably reinforced by Mussolini being an amateur violinist.

Hitler was attracted by Mussolini’s fascism for the way it centralized power, and Mussolini saw an ally in the aggressive Hitler to help lead the way to a world under their shared power. Hitler propped up Mussolini when the Italians were generally opposed to his Fascist regime. Most historians believe that Hitler had genuine affection for the man. Mussolini coined the idea of Europe spinning on a new axis, linking Berlin and Rome, in November 1936, while announcing a friendship alliance with Germany: “This Berlin-Rome protocol is not a barrier, it is rather an axis around which all European States animated by a desire for peace may collaborate on troubles.”

By 1940, Hitler was calling the shots. Mussolini hesitated to join the war, and only declared war on France (July 10, 1940) when it was clear that the underprepared Italians would be riding the coattails of the Germans. The occupation was over so quickly that the Italians did not even have a chance to score a victory. At a meeting between the leaders, Mussolini’s foreign secretary and son-in-law, Count Ciano, said that Il Duce’s opinion had “only a consultative value.” Indeed, from then on Mussolini was obliged to face the fact that he was the junior partner in the Axis alliance, and was not consulted on military decisions until after the fact.

It was to “pay back Hitler in his own coin,” as Mussolini openly admitted, that he decided to attack Greece through Albania in 1940 without informing the Germans. But it was too much for the Italians to handle and Germany came to their aid to clean up the mess. The 1941 campaign to support the German invasion of the Soviet Union also failed disastrously and condemned thousands of ill-equipped Italian troops to a nightmarish winter retreat. Mussolini set his sights on North Africa and extending his Empire to match the territory held by the ancient Romans, whose conquests he desired to copy.

British troops were in North Africa under a 1936 treaty, stationed in Egypt to protect the Suez Canal and Royal Navy bases. Hitler had offered to aid Mussolini early on in his North African quest, to send German troops to help fend off a British counterattack. But Mussolini had been rebuffed when he had offered Italian assistance during the Battle of Britain. He now insisted that as a matter of national pride, Italy would have to create a Mediterranean sphere of influence on its own–or risk becoming a “junior” partner of Germany’s.

Mussolini’s forces proved no match for the Brits. British troops pushed the Italians westward, inflicting extraordinary losses on the Axis forces. On February 5, 1941, Adolf Hitler scolded his Axis partner, Benito Mussolini, for his troops’ retreat in the face of British advances in Libya, demanding that the Duce command his forces to resist. As Britain threatened to push the Italians out of Libya altogether and break through to Tunisia, Mussolini swallowed his pride and asked Hitler for assistance. On February 12, German General Erwin Rommel arrives in Tripoli, Libya, with the newly formed Afrika Korps, to reinforce the beleaguered Italians’ position.

As the modern writers put it:

“Benito Mussolini has been universally regarded as an almost comical stereotype of a blundering dictator, a petit-bourgeois hick from the provinces who played a distant second fiddle to his powerful ally Adolf Hitler, and whose inept leadership and lust for power led Italy to disaster.” – RJB Bosworth

“Their relationship evolved gradually over the years they had known each other. At first, Hitler deferred to the Duce and appeared to have genuine admiration for the more senior dictator. Later, and especially after Mussolini began to play second fiddle to Hitler as a war leader, summit meetings between the two men had consisted mainly of long monologues by Hitler, with Mussolini barely able to get in a word. At one memorable meeting in 1942, Hitler talked for an hour and forty minutes while General Jodl dozed off and Mussolini kept looking at his watch.” – Ray Moseley

After Hitler’s rise to power, Mussolini almost always played second fiddle to Hitler in their joint venture. Aside from a brief span of time in which Mussolini stood in the way of Hitler’s plans to seize Austria, the Italian dictator seems to have been all too willing to accept Hitler’s flattery and praise, while at the same time watching his Axis ally drag him into a war that he couldn’t hope to win. During the many times that the two dictators met, Shirer says that Hitler did all the talking and Mussolini all the listening.

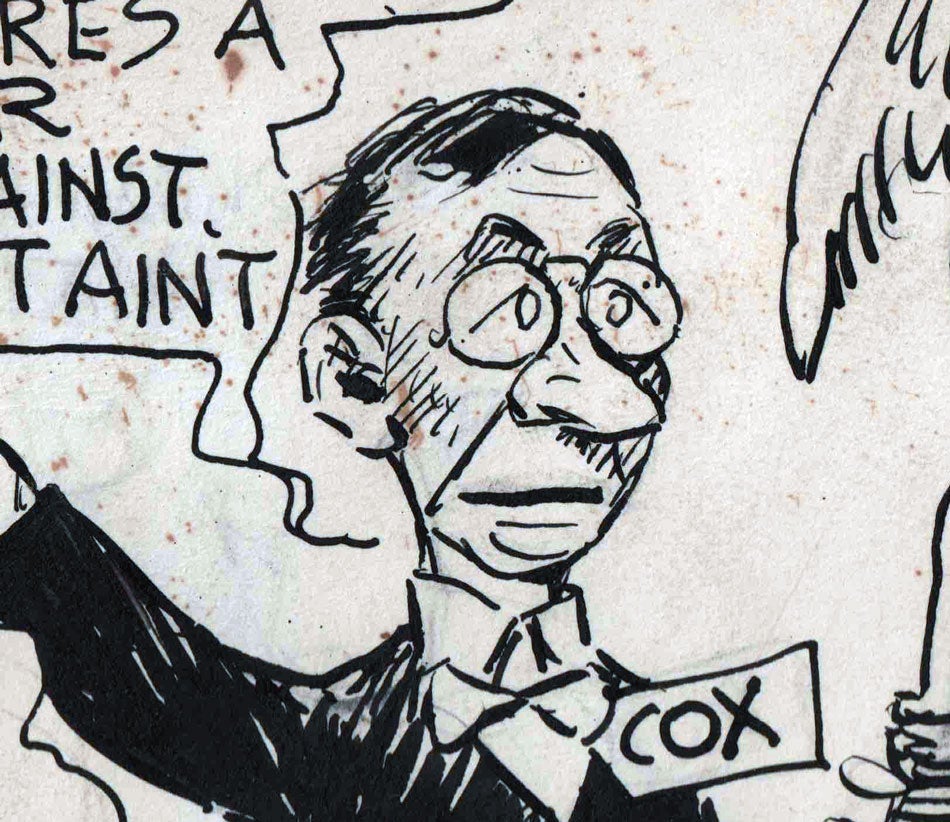

“What a Headache We’re Building Up” (July 5, 1941)

“What a Headache We’re Building Up” (July 5, 1941)

1940.10.08 “So Am I!” (October 8, 1940)

1940.10.08 “So Am I!” (October 8, 1940)

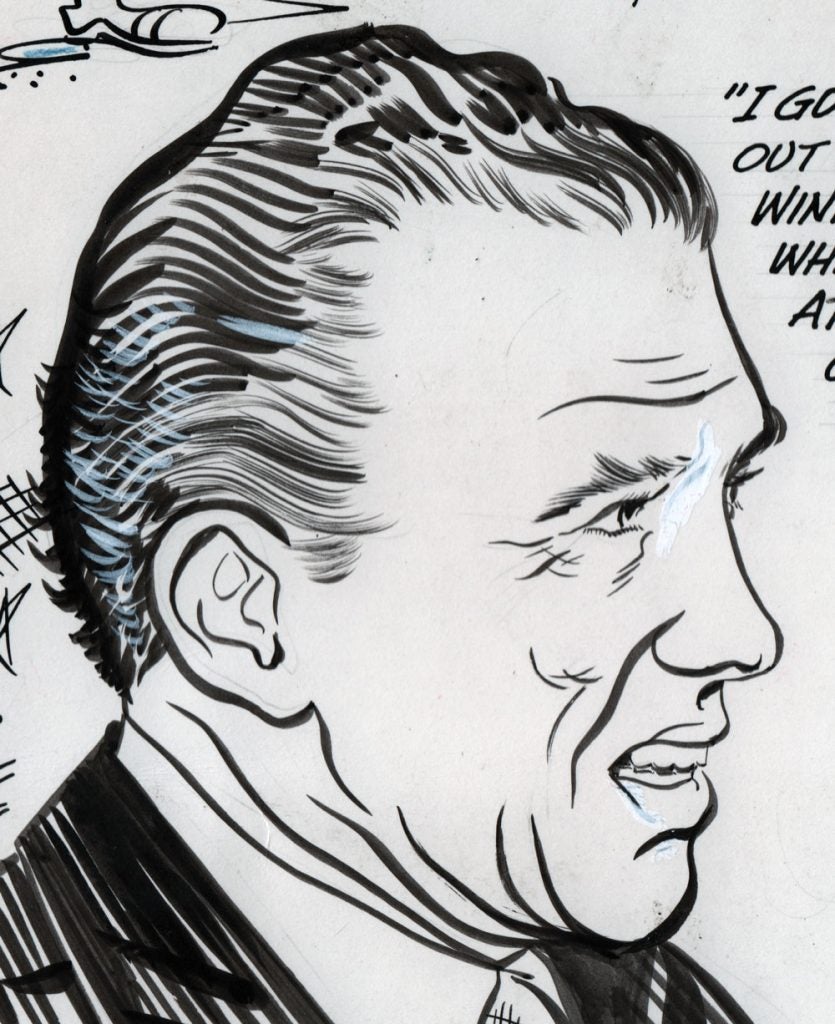

“Ed Sullivan (signed) Celebrates His 9th Anniversary” (September 23, 1956)

“Ed Sullivan (signed) Celebrates His 9th Anniversary” (September 23, 1956)