I have been buying (and making modest suggestions for the design of) jewelry from an awesome Neo-Modernist named Daniel Macchiarini (1954-) since the late 1990s. Danny is the son of Peter Macchiarini, who was a key fixture in the San Francisco artist scene in the North Beach area of San Francisco from the 1930s to the time of his death in the 1990s. Feel free to visit Danny (virtually or in person) at:

Macchiarini Design

1554 Grant Ave.

San Francisco, CA 94133

Phone: 415.982.2229

Email: danny1mac@sbcglobal.net

Store web site: http://www.macreativedesign.com

anYhOw… thanks to my pent-up desire to do 3D art, which I had never done, and my respect for Danny, and his own pent-up desire to begin to think about offering workshops, we agreed to set a time to see how we might resolve this clearly mutual creative interest. And we did, over the weekend of March 20-21, 2005.

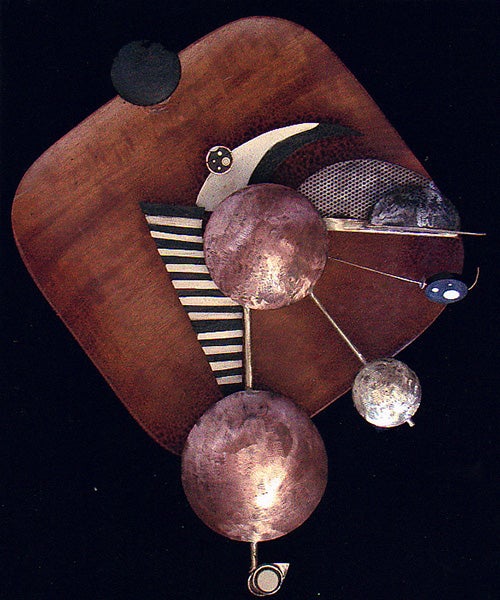

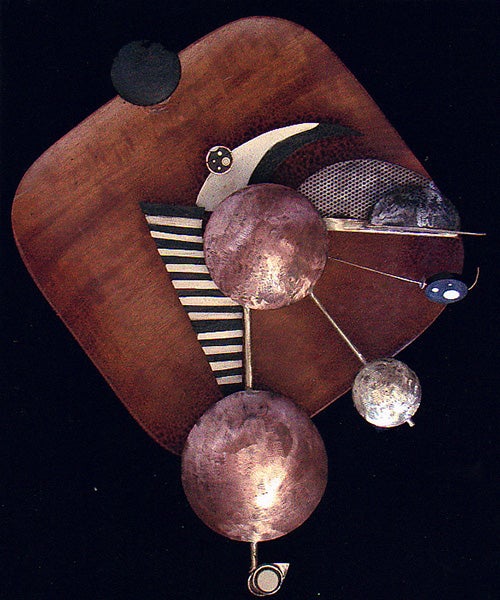

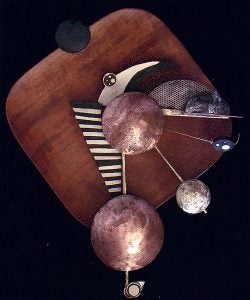

“Oppenheimer’s Dharma” (2005)

by Brian P Coppola

assisted by Ian Stewart

directed by Daniel Macchiarini

Materials: Ebony, Ivory, Mahogany, Copper, Brass, Stainless Steel, Mild Steel

Created in a Sculpture Workshop (20-21 March 2005) conducted by Daniel Macchiarini @ Macchiarini Creative Design Studio, San Francisco, CA

The Story

Former UM undergrad and Berkeley PhD Ian Stewart, who has been known to drop a peso or two at Macchiarini’s place, joined in the fun on that March 20.

Day One (noon): A brief lesson from Danny, on his computer, about space, shape, texture, balance, and other fundamental art ideas, using images and examples of his and his father’s pieces as a resource. Then, Ian and I got a user’s tour of the workshop, and a big old blank spot at a workbench… a large sheet of newsprint, some pencils, and lots of metal and wooden objects to think about as we played “the game of the sculpture.” This is a fun game and takes at least two players: laying out shapes and developing a single drawing as you talk out loud about your ideas. On another day, maybe, I will give a more detailed version of the process. But, once the ideas began to converge as an array of objects whose relationship started to be fixed (around 2-3 pm), Danny (who was just hanging back and mainly answering questions) showed us how to cut and solder different types of metals, and to deal with the other technques that we needed to learn.

In the Neo-Modernist tradition, the plan evolves through iteration: you do not always know the whole story first – it emerges. Most of the basic story emerged for me by the time we started soldering (although I did not share it), and the sculpture itself continued to emerge as the story refined itself in my mind. Yeah – you will be hearing about it soon enough. We worked until about 6 pm.

Day Two (10 am): Just me and Danny. I worked on my sculpture, learned to work with ivory and ebony, and bantered around with Danny while he worked on a large fountain/sculpture that was to be installed in someone’s backyard garden. By about 4 pm, the sculpture was done (except for polishing) and being hung on the wall. I went over to the newsprint design and wrote the title next to the drawing: “Oppenheimer’s dharma.” A client of Danny’s came into the store, and Danny was all “Look what Brian did at this workshop we just finished.” And the client was all “Nice, interesting, whatever.” And I was all “You guys want to know the title and the story of this piece?”

Heh heh heh – Danny tends to sculpt and design in large sweeping ideas and motion, rather than in descriptive narrative, so I think he was at least a little surprised when I had this story to tell.

“Oppenheimer’s dharma”

by Brian P Coppola

San Francisco, CA; 03/21/05

To a Hindu, one’s dharma is the “law” or “job” of your position in life: the responsibilities you have as a member of your caste. In contrast with your karma, which is the report card of how well (or not) you did in fulfilling your dharma. One of the reasons why Robert Oppenheimer might have become enamored with Hindu texts, particularly the Bhagavad Gita, was that it helped him reconcile his scientist’s dharma (to discover and always push forward) when faced with the moral dilemma of helping to create a device (the Bomb) that he understood to be morally indefensible and reprehensible. When seeing the flash and the mushroom cloud at the Trinity test site, Oppenheimer is reported to have quoted from the Gita: “I am become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds.”

In “Oppenheimer’s Dharma” I have depicted a classic creation/death/resurrection cycle.

You can start reading this anywhere, but let’s start at the bottom. A drop of pure white (circular ivory) combines with the void, continuing (because starting has no meaning) the universal cycle (and it moves in the direction of the arrow, in case you need help). Time passes, as suggested by a pendulum swing, the action of a clock – of time. Eventually, worlds form. Inherently nihilistic, creation is accompanied by destruction. The creation (vertical) axis complements the destruction (horizontal) axis: they are not opposites; together they comprise the whole. Nearly at the horizontal, a world explodes.

You can start reading this anywhere, but let’s start at the bottom. A drop of pure white (circular ivory) combines with the void, continuing (because starting has no meaning) the universal cycle (and it moves in the direction of the arrow, in case you need help). Time passes, as suggested by a pendulum swing, the action of a clock – of time. Eventually, worlds form. Inherently nihilistic, creation is accompanied by destruction. The creation (vertical) axis complements the destruction (horizontal) axis: they are not opposites; together they comprise the whole. Nearly at the horizontal, a world explodes.

It always happens: the Bomb. It’s a dirty dharma, but someone has to do it: the shock wave and the mushroom cloud appear. The explosion echoes along history’s path, and creation rises from destruction in the form of the phoenix – purifying and refining in the fires of creation and destruction. Worlds die, but the movement of history goes on (the arc continues), and new worlds arise in the eye of the phoenix. Destruction is cast out in the form of the blackness (in creation, sometimes destruction is destroyed), emerging from the same direction as the refined white teardrop of the phoenix. Darkness and light continue their  battle in the body of the phoenix until at last there is only the void, again, along with the pure white tear (or is it the seed?) of the phoenix. Pure white combines with the void, continuing the universal cycle.

battle in the body of the phoenix until at last there is only the void, again, along with the pure white tear (or is it the seed?) of the phoenix. Pure white combines with the void, continuing the universal cycle.

The creation/death/resurrection cycle requires all players to play their parts. Oppenheimer’s dharma is not merely that of a scientist; his dharma – and his uniqueness – is that of the scientist who must inevitably build the Bomb.

The destruction of destruction, after all, is creation.

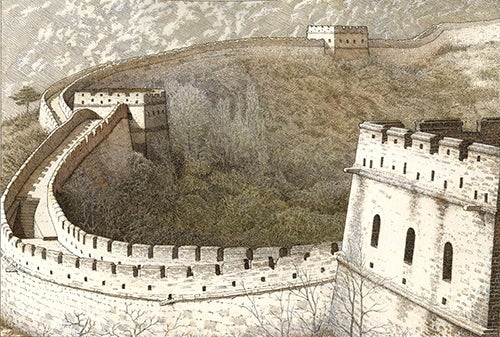

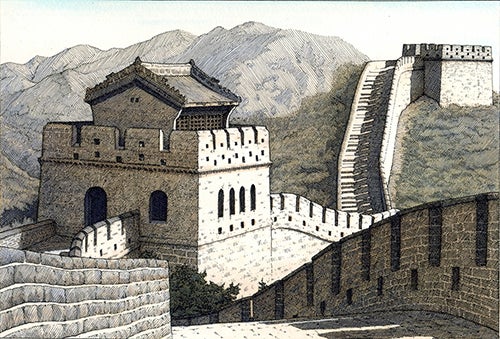

“Great Wall No. 1” (2009)

“Great Wall No. 1” (2009)

You can start reading this anywhere, but let’s start at the bottom. A drop of pure white (circular ivory) combines with the void, continuing (because starting has no meaning) the universal cycle (and it moves in the direction of the arrow, in case you need help). Time passes, as suggested by a pendulum swing, the action of a clock – of time. Eventually, worlds form. Inherently nihilistic, creation is accompanied by destruction. The creation (vertical) axis complements the destruction (horizontal) axis: they are not opposites; together they comprise the whole. Nearly at the horizontal, a world explodes.

You can start reading this anywhere, but let’s start at the bottom. A drop of pure white (circular ivory) combines with the void, continuing (because starting has no meaning) the universal cycle (and it moves in the direction of the arrow, in case you need help). Time passes, as suggested by a pendulum swing, the action of a clock – of time. Eventually, worlds form. Inherently nihilistic, creation is accompanied by destruction. The creation (vertical) axis complements the destruction (horizontal) axis: they are not opposites; together they comprise the whole. Nearly at the horizontal, a world explodes.

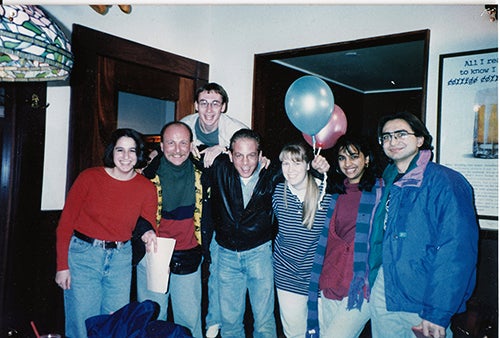

The 2016-17 leaders in the University of Michigan Structured Study Group (SSG) program for Organic Chemistry, Feb 2017, wishing me a happy birthday from the dinner I could not attend because I was out of town [l to r: James, Jenny, Jack, Danny (middle), Mike (back), Thomas, Charles (front)]

The 2016-17 leaders in the University of Michigan Structured Study Group (SSG) program for Organic Chemistry, Feb 2017, wishing me a happy birthday from the dinner I could not attend because I was out of town [l to r: James, Jenny, Jack, Danny (middle), Mike (back), Thomas, Charles (front)]

“Tales of Suspense #86: Iron Man p 11” (February 1967)

“Tales of Suspense #86: Iron Man p 11” (February 1967)