con grande grazie a Liberato Cardellini (traduzione)

Dipartimento SIMAU, Via Brecce Bianche, 12 – 60131 Ancona, Italy

L’antefatto

La famiglia di mio padre emigrò negli Stati Uniti intorno al 1900, dalla Sicilia, dove hanno vissuto fin dagli inizi del ‘600. In quel periodo, per la maggior parte del tempo, hanno abitato nella città costiera di Aci Catena, nella parte est della Sicilia. Prima di lasciare l’Italia, il mio bisnonno ha imparato il mestiere di fabbricare i sigari, e la famiglia ha intrapreso questo commercio quando è arrivata negli Stati Uniti.

Sono sempre stato un grande ammiratore del grande artista grafico, Alphonse Mucha. Era vivente e al lavoro a cavallo del secolo, spesso facendo manifesti stellari per la pubblicità.

Entra ora Esteban Maroto, un artista spagnolo contemporaneo che ha fatto numerose opere d’arte nei generi fantascienza e fantasia. Una delle sue opere ha attirato la mia attenzione: un manifesto pubblicitario in cui mi sono imbattuto. Immediatamente questo disegno mi ha spinto a contattare Esteban e proporre un comitato: cosa succede se Mucha avesse fatto alcuni manifesti pubblicitari per quei straordinari produttori di sigari siciliani, i Fratelli Coppola di Aci Catena?

Esistono delle foto della vetrina dei produttori Fratelli Coppola nella loro location degli Stati Uniti. La più antica è del 1903, quando parecchi di loro sono immigrati.

Qualche tempo dopo, come si può vedere nella prossima foto, il negozio è meglio costruito, e l’immagine completa del negozio di sigari mostra una statua, con la mano destra alzata e, presumibilmente tenendoci un sigaro. È un po’difficile da vedere, ma al centro della grande insegna sopra la porta è riportata una triskele (triscele), che è il simbolo al centro della bandiera siciliana.

Nel 1938, il negozio ha continuato ad evolversi, e il nostro amico ha perso il suo braccio destro. Le prossime due immagini sembrano essere contemporanee.

I sigari siciliani sono noti per la loro forma e dimensione, e per lo stile unico dei loro nastri che avvolgono i sigari, che sono oggetti da collezione.

L’idea

Volevo due poster, come se la campagna pubblicitaria potesse occupare le pagine faccia a faccia in una rivista, o che potessero essere visualizzati fianco a fianco come manifesti attuali. I pezzi fondamentali delle informazioni visive, ho proposto ad Esteban, avrebbero dovuto essere:

(1) doppi; i due manifesti avevano bisogno di essere uniti, tematicamente, così maschile e femminile è stata una scelta ovvia, con entrambi in abiti carnevaleschi esagerati

(2) storici; (a) la statua del ragazzo del negozio di sigari sarebbe stata una figura importante da integrare in qualche parte del poster; (b) il nome dello stabilimento, e il suo anno di fondazione fittizio, 1851, l’anno di nascita del mio bisnonno; (c) riportare la fascia che avvolge i sigari dei Fratelli Coppola, con la triskele, richiamando l’eredità siciliana, anche questa una finzione completa

L’esecuzione

Esteban rimuginò le mie richieste per un po’ e mi propose un grande piano. Avrebbe ampliato la dualità dell’uomo e della donna incorporando il sole e la luna con una tavolozza di colori corrispondentemente caldi e freddi. Ha mandato i disegni che seguono. Quello della donna era quasi perfetto (sbarazzarsi del bicchiere di champagne), e il logo avrebbe dovuto essere una rappresentazione più letterale di un nastro del sigaro.

Non mi importava della composizione del manifesto dell’uomo. Era troppo verticale e diviso, rigido, e non complementare al flusso eccezionale del manifesto della donna. Il tema del sole e della luna insieme è una grande idea, e si può vedere il vortice solare. L’integrazione della figura in uno solo dei manifesti piuttosto che in entrambi mi è molto piaciuta, e si può vedere l’inizio di quello che sarà un rapporto formidabile tra la figura e l’uomo.

Mi sono limitato a suggerisce l’idea di fare in modo che risultassero come una coppia e la congruenza del flusso compositivo; Esteban ha fatto il resto. E il ragazzo ha fatto centro. Ho pensato che la revisione era semplicemente grande. L’uomo ha perso il suo drink e il suo sigaro, e ora il ruolo del sole è quello di accendere il sigaro della figura. Semplicemente geniale!

La fanciulla parzialmente completata è arrivata per prima. È una composizione stupenda, con la sua marcata diagonale completamente integrata con il moto circolare del resto della pagina.

Quando l’uomo è arrivato, ho capito però che avevo fatto un errore. Avevo chiamato la figura del negozio di sigari una statua, e questo è stato un errore. Secondo quanto mi ha detto Esteban, il grigio è stato intenzionale, e non ho pensato che tanto contrasto avrebbe potuto funzionare.

Esteban ha voluto fare un tentativo, e ha promesso di pensare alla luce e ai riflessi. Il maggiore contrasto interno si presenta meglio, ma nel complesso il contrasto nella composizione non è stato, per me, una idea vincente.

Ho voluto dargli un paio di opzioni. Una idea era quella di attenersi alla statua monotono, ma di colmarla con i riflessi giallo-arancio che avrebbe dovuto da questo colore riflesso. Suppongo che non avremmo mai potuto sapere, da queste vecchie immagini, se la figura era dipinta oppure no, ma il look oltraggioso delle Guardie del Vaticano è un classico italiano. Per me, la campagna pubblicitaria vorrebbe il nostro amico in un abito pieno di colore; questa era la mia preferenza.

Esteban l’ha azzeccato!

“Fratelli Coppola (La Luna)” (2017)

“Fratelli Coppola (La Luna)” (2017)

di Esteban Maroto (1942-)

20 x 26 in., inchiostro, pennarello, acrilico e acquerello su carta pesante

Collezione Coppola

“Fratelli Coppola (Il Sole)” (2017)

“Fratelli Coppola (Il Sole)” (2017)

di Esteban Maroto (1942-)

20 x 26 in., inchiostro, pennarello, acrilico e acquerello su carta pesante

Collezione Coppola

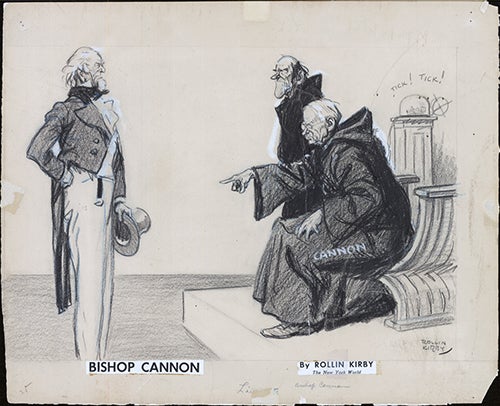

“Bishop Cannon” (ca. 1927)

“Bishop Cannon” (ca. 1927) “Crusader” (ca. 1941-42)

“Crusader” (ca. 1941-42) “Eventually” (September 22, 1942)

“Eventually” (September 22, 1942)