Honorius (minted 395-402 CE)

Honorius (minted 395-402 CE)

Mint: Mediolanum (Milan)

4.4g gold, 21 mm

RIC X 1206; Sear 20916

Provenance: James H Cohen (NOLA)

Coppola Collection

“I wonder if the Emperor Honorius, watching the Visigoths coming over the seventh hill, could truly realize that the Roman Empire was about to fall. This is really just another page of history, isn’t it? Will this be the end of our civilization?” (Captain Jean-Luc Picard, to Guinan, anticipating the Borg attack in Star Trek: The Next Generation “The Best of Both Worlds I,” the third season’s finale, broadcast June 18, 1990)

Honorius (Flavius Honorius Augustus; 9 September 384 – 15 August 423 CE) was Western Roman Emperor from 393 to 423 (age 9-39). He was the younger son of emperor Theodosius I and his first wife Aelia Flaccilla, and brother of Arcadius (b. 377), who was the Eastern Emperor from 395 until his death in 408 (age 18-31).

The most notable event of Honorius’s reign was the assault and Sack of Rome on August 24, 410 by the Visigoths under Alaric. Rome had not been attacked in almost 800 years. At that time, Rome was no longer the capital of the Western Roman Empire, having been replaced in that position first by Mediolanum in 286, where this coin was minted, and then by Ravenna in 402, where other versions of the Honorius coin were minted.

Stilicho, Honorius’s principal general, was both Honorius’s guardian (during his childhood) and his father-in-law (after the emperor became an adult). Stilicho’s generalship helped preserve some level of stability, but with his execution in 408, the Western Roman Empire moved closer to collapse.

Rome was under siege by the Visigoths shortly after Stilicho’s deposition and execution. Lacking his strong general to control the by-now mostly barbarian Roman Army, the indecisive Honorius could do little to attack Alaric’s forces directly, and apparently adopted the only strategy he could in the situation: wait passively for the Visigoths to grow weary and spend the time marshaling what forces he could.

Honorius died of edema on 15 August 423, leaving no heir.

The Western Empire fell in 476 CE after the one-year reign of Honorius’s ninth successor, Romulus Augustus. His deposition by Odoacer, a soldier who became the first king of Italy, typically marks the end of ancient Rome and the start of the Dark/Middle Ages.

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire and Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire in the East, starting from ca. 300 CE, and through the Dark/Middle Ages and the Crusades, when its capital city, Constantinople (Istanbul), fell to the Turks in 1453, following the rise of the Ottoman Empire, which began in 1300.

This is really just another page of history, isn’t it? Will this be the end of our civilization? — turn the page.”

1866 Great Britain Young Queen Victoria Gold Sovereign

1866 Great Britain Young Queen Victoria Gold Sovereign Bactrian Ring with black/brown stone (ca. 1600 CE)

Bactrian Ring with black/brown stone (ca. 1600 CE)

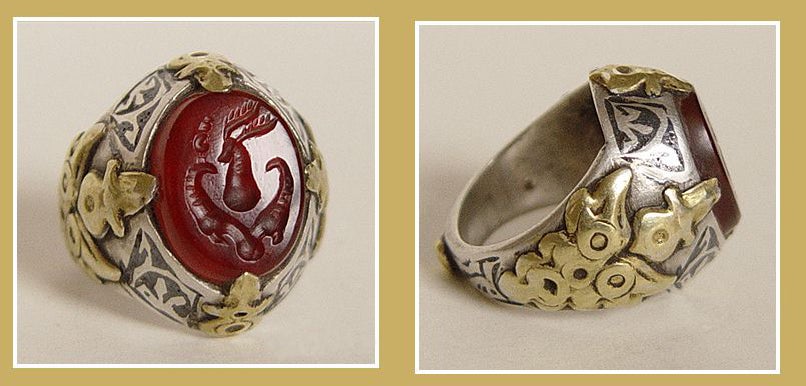

Persian Ring with Deep Red Carnelian Stone (ca. 1750 CE)

Persian Ring with Deep Red Carnelian Stone (ca. 1750 CE)

Taras or Tarentum, in Calabria, Southern Italy (300-280 BCE)

Taras or Tarentum, in Calabria, Southern Italy (300-280 BCE)

Sempronius Pitio Roman Republic Denarius (minted 148 BCE)

Sempronius Pitio Roman Republic Denarius (minted 148 BCE) Chihongo (Spirit of Wealth) Chokwe Tribal Mask (Angola)

Chihongo (Spirit of Wealth) Chokwe Tribal Mask (Angola)

Caesar (minted 49-48 BCE)

Caesar (minted 49-48 BCE)

Honorius (minted 395-402 CE)

Honorius (minted 395-402 CE) British-found Roman Ring (ca. 20 CE)

British-found Roman Ring (ca. 20 CE)