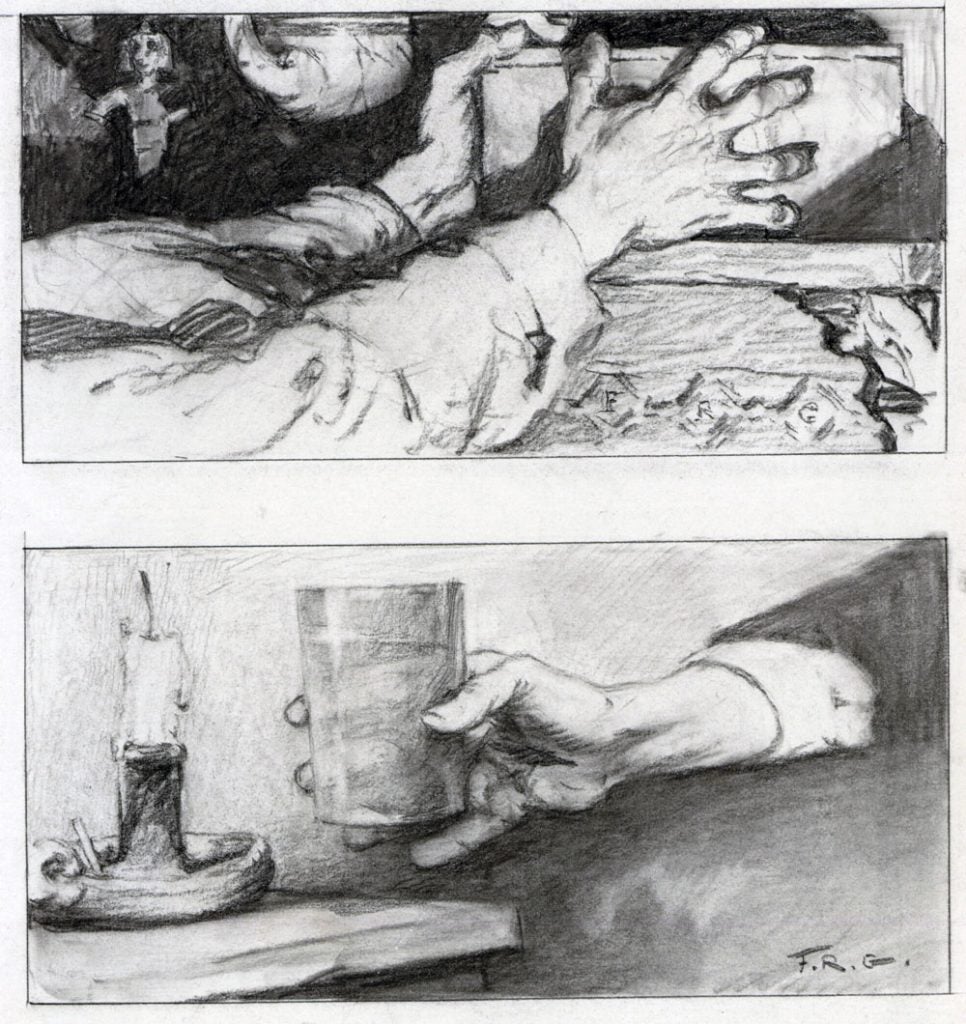

Hands, from “Murder in Mesopotamia” (1935, Part 5)

by Frederic Rodrigo Gruger (1871-1953)

7 x 6 in., pencil on board

Coppola Collection

Saturday Evening Post

by Agatha Christie (12/7/1935; pp 28-29)

“Murder in Mesopotamia” (Agatha Christie ) was first published in a 6-part serialized form in The Saturday Evening Post (Nov.9-Dec.14 1935), and was illustrated by FR Gruger.

Gruger, a master of photorealism in pencil-strokes, contributed artwork to various magazines and for the works of more than 400 authors. In 1928, The Saturday Evening Post published a cartoon about Gruger, dressed as a knight in armor to defend the secret of his famous drawing technique.

He was one of the most highly regarded and prolific illustrators of the day. In 1939, Time proclaimed him “the dean of U.S. magazine illustrators.” Norman Rockwell looked up to him as “one of our greatest illustrators.” His work appeared everywhere — he created an astonishing 6,000 illustrations between 1898 and 1943, but his true home was with the Post, for which he did thousands of illustrations. The same Time article stated, “After 1899 when George Horace Lorimer became editor of The Saturday Evening Post, Gruger became the mainstay of that magazine. The Post’s romantic and period fiction…got half its atmosphere from Gruger’s old fashioned, deep-browed men and frail but credulous women.”

Surprisingly, his technique was just drawing with a pencil on cheap cardboard. When Gruger first began working on the staff of a newspaper, he learned to draw on flimsy cardboard called “railroad blank.” The newspapers kept stacks of railroad blank lying around for anyone to use as a backing for photos. The cardboard was so cheap, nobody cared how much Gruger borrowed to practice his drawing. He experimented with smearing and erasing the carbon pencil to achieve special effects that no one else had achieved. Pretty soon, he became a virtuoso of pencil and cardboard. Railroad blank was renamed “Gruger board” in recognition of the astonishing work that Gruger was able to perform on it.