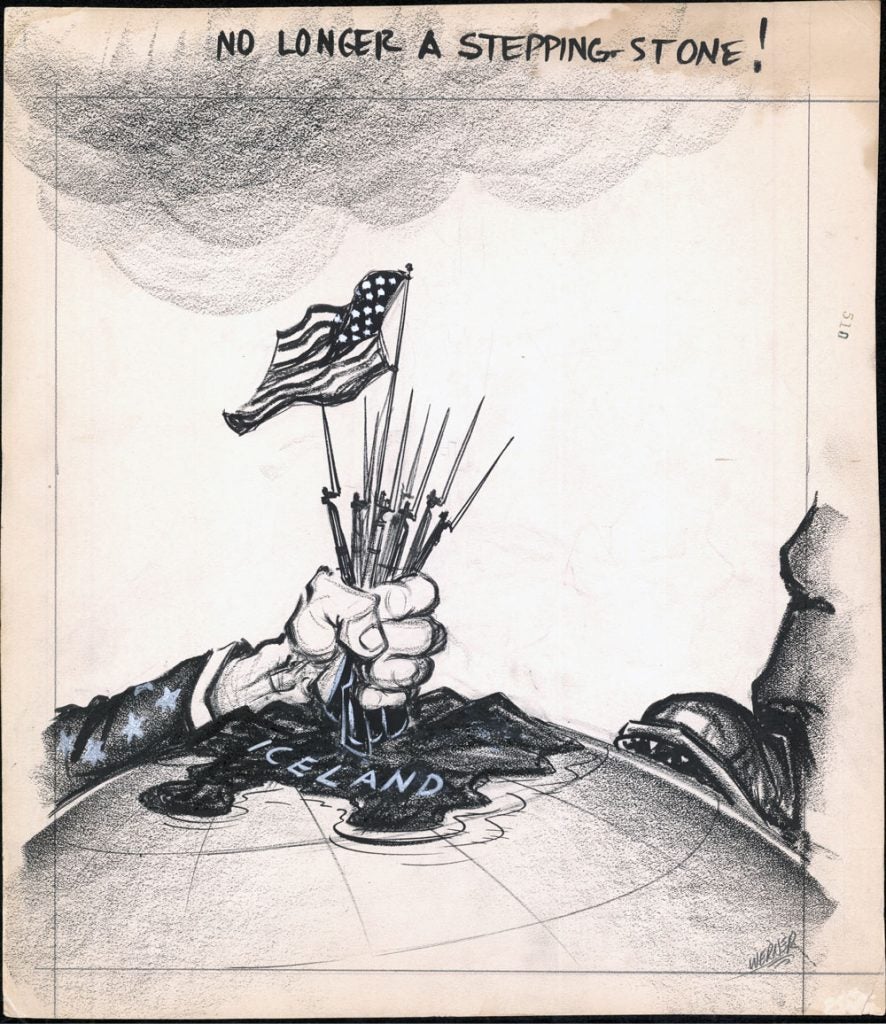

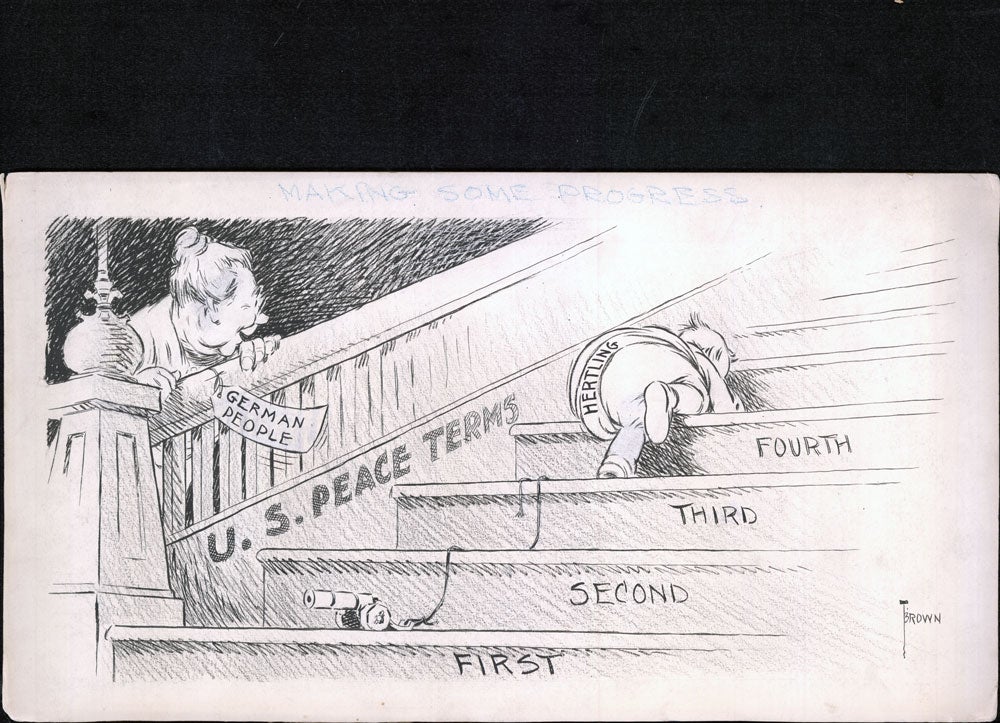

“Making Some Progress” (September 22, 1918)

by Edward Scott “Ted” Brown (1876-1942)

12 x 20 in., ink on board

Coppola Collection

One cartooning historian describes Brown as “an absolute whirling dervish at the drawing board, producing more material for the daily pages than anyone except the great George Frink.” Brown worked for the “Chicago Daily News” (ca. 1908-24) and the “New York Herald-Tribune” (1925-42).

Ted Brown, who spent his early years chasing the Alaska gold rush of 1898, returned to the US with no gold score and was a longtime editorial cartoonist for the New York Herald-Tribune, supplanting Jay N. (Ding) Darling in that position. Brown took ill in mid-1942 and died in late December.

The Fourteen Points speech of President Woodrow Wilson was delivered before a joint meeting of Congress on January 8, 1918, during which Wilson outlined his vision for a stable, long-lasting peace in Europe, the Americas and the rest of the world following World War I.

From October 1917 to October 1918, the German Chancellorship was in the hands of Count Georg von Hertling. The Fourteen Points speech was in line with the Reichstag’s Peace Resolution.

“The program of the world’s peace, therefore, is our program; and that program, the only possible program, as we see it, is this:

“I. Open covenants of peace, openly arrived at, after which there shall be no private international understandings of any kind but diplomacy shall proceed always frankly and in the public view.

“II. Absolute freedom of navigation upon the seas, outside territorial waters, alike in peace and in war, except as the seas may be closed in whole or in part by international action for the enforcement of international covenants.

“III. The removal, so far as possible, of all economic barriers and the establishment of an equality of trade conditions among all the nations consenting to the peace and associating themselves for its maintenance.

“IV. Adequate guarantees given and taken that national armaments will be reduced to the lowest point consistent with domestic safety.”

In mid-August 1918, German troops began retreating on the Western Front and in the second half of September 1918, Germany’s Turkish, Bulgarian, and Austrian allies acknowledged defeat and asked the Allied powers for a ceasefire.

On September 29, 1918, the German high command, Hindenburg and Ludendorff, finally disclosed to the Kaiser that the military situation was desperate and that the war could not be won. In the face of this admission of defeat they demanded two things: The civilian government was to ask US President Wilson for the terms of an armistice on the basis of his Fourteen Points and, at the same time, the imperial constitution should be reformed to include the political parties in government responsibility.

Chancellor Hertling did not accept the demands for democratic reform and handed in his resignation.

The Armistice of November 11, 1918 ended fighting on land, sea and air in World War I between the Allies and Germany. It came into force at 11:00 a.m. Paris time… on this day, at the 11th hour on the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918, the Great War ends.